A labor shortage is hitting Cincinnati. These nonprofit groups are responding with inclusion.

Three organizations demonstrate the lesson that employment that lasts does not begin at the moment of hire. It begins earlier with time, structure and intention.

At 2:30 in the afternoon, the cafe door is locked even though the lights are on. A handwritten sign taped to the glass apologizes for the early closure. Down the block, a construction crew is short two workers and a project timeline slips another week. Across the region, these scenes are becoming familiar.

There is a labor shortage unfolding across Greater Cincinnati, and it is no longer abstract. It shows up in shortened business hours, delayed services, and employers quietly admitting they cannot find people to do the work that keeps communities functioning. While the causes are often discussed broadly, the pressure is being driven by a combination of demographic shifts, retirements, and immigration crackdowns that have removed workers from the local economy.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Cincinnati metropolitan area has hovered below four percent unemployment through late 2025, a level economists consider near full employment. In practical terms, most people who want a job already have a job. Yet job openings remain high across healthcare support roles, food service, construction, warehousing, cleaning services, and customer-facing industries. Employers are competing for a shrinking pool of workers.

That strain is not evenly distributed. Immigration enforcement and deportations have hit specific sectors particularly hard, especially food service, construction, landscaping, warehousing, cleaning services, and caregiving roles. These industries have long relied on immigrant labor, often in physically demanding or lower-wage positions that already struggle with retention. When workers are removed abruptly, the effects ripple outward. Shifts go uncovered and projects slow. Businesses shorten hours or reduce services. In many cases, there is no immediate replacement workforce waiting to step in.

What employers are confronting now is not simply a lack of applicants, but the consequences of a labor system that depended on invisible workers without building redundancy or inclusion into its hiring practices. As those pipelines collapse under enforcement pressure, the gaps become visible. The work still needs to be done. The question is who will be supported and allowed to do it.

For some organizations in the region, that question has shaped their work for years.

At Starfire Council, employment does not begin with a job opening. It begins with the person. Rather than placing individuals into predefined roles, staff start by understanding interests, skills, sensory needs, routines, and long-term goals, then work outward from there.

Much of that process happens long before a résumé is submitted or an interview scheduled including informational interviews, relationship-building with employers, and exposure to different work environments. Conversations resist the idea that success should be measured by speed alone.

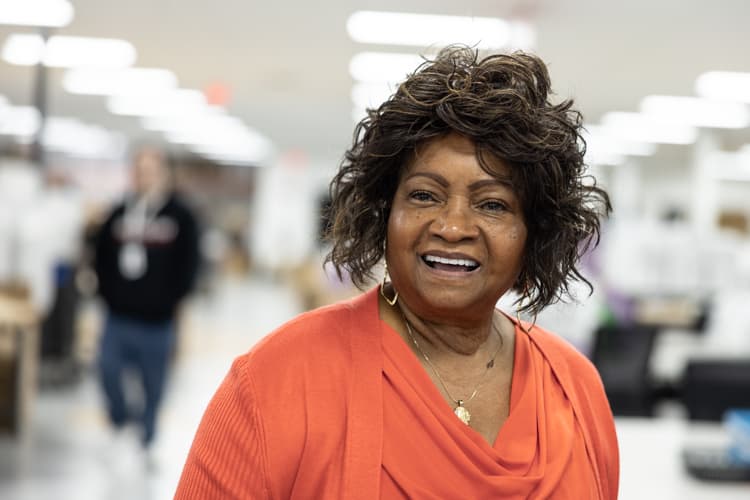

Carol Buckner, founder of Buckner Employment Service and Training (BEST), who works directly with individuals through Starfire, describes employment as a process rather than a placement. The goal is alignment, not volume. That often means helping employers rethink assumptions about productivity, fit, and what a qualified worker looks like in practice.

Buckner is careful about where the focus lands. She said the work is not about centering disability, but about identifying ability. Too often, systems are designed to catalog limitations rather than recognize skills. Starfire’s approach flips that logic. The question becomes what someone can do well, what environments support that ability, and how employers can meet people there.

That shift changes the conversation for everyone involved. Individuals are no longer asked to prove they belong. Employers are no longer asked to take a leap of faith. Both are invited to focus on capability, fit, and contribution rather than diagnosis or deficit.

Inclusive employment, Buckner acknowledged, often takes longer on the front end. It requires more conversation and patience than traditional hiring. For employers used to filling positions quickly, that can feel like a risk.

But the long view tells a different story. When the fit is right, employers often gain an employee who stays for years rather than months. Turnover drops and stability improves. The time invested up front is recouped in ways many employers say they are struggling to find elsewhere.

That same long view shapes the work at Easterseals Redwood, which has grown into one of the region’s largest workforce and service organizations. What began as a small effort to support people with disabilities has expanded into programs that include workforce development, behavioral health services, and support for veterans and families.

Today, much of Easterseals Redwood’s staff includes people with disabilities themselves, along with veterans, parents returning to the workforce, and caregivers navigating complex lives alongside their jobs. Rather than treating disability or life circumstance as a limitation, the organization has built systems around flexibility, accommodation, and skill alignment. The goal is not to remove expectations, but to make work accessible and sustainable.

Veterans bring leadership and adaptability shaped by service. Parents bring time management and resilience honed outside traditional workplaces. Disabled employees bring deep expertise in navigating systems that were never designed for them. In a labor market defined by disruption, that experience has become an asset rather than an exception.

Nathan Davis, military and veterans center operations manager at Easterseals Redwood, said employers often focus on what veterans lost rather than what they still carry with them. “Although they may have service-connected disabilities, they still have all the skills they brought from the military,” Davis said. Leadership. Mission focus. The ability to build camaraderie inside a team. “Those things are still there.”

For veterans in particular, Davis said employment is about more than income. “When you have a job, you have a mission,” he said. Outside the military, that sense of purpose often has to be rebuilt. Work, when paired with support and team structure, can be the place where that clarity begins again.

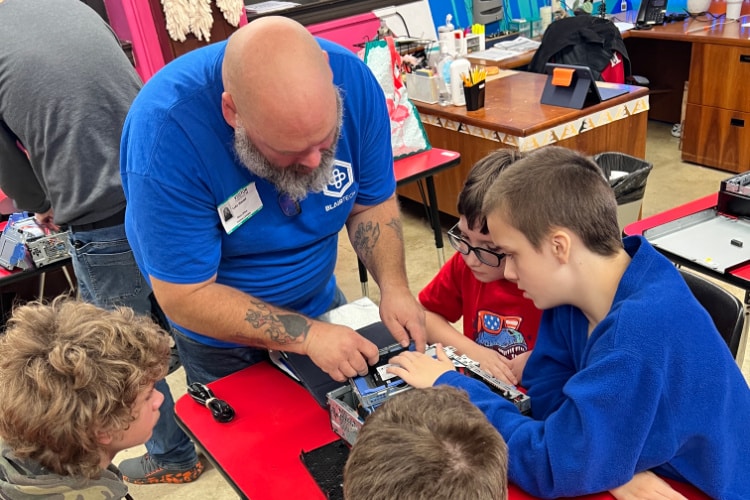

The results of that behind-the-scenes work become visible at Point Perk Coffee, located at the intersection of Pike and Washington streets. The cafe is one of several business ventures operated by The Point Arc, each designed to function as a real workplace rather than a temporary training site. Through paid employment, staff develop practical, transferable skills, including customer interaction, time management, and collaboration with coworkers. The emphasis is not on short-term placement, but on building habits and experience that carry into future employment.

That culture takes shape on the floor. Point Perk manager Rachelle Ungerman described a workplace defined less by policy than by personality. “Our individuals shape our culture, not only by their presence, but by their individual personalities,” she said. Customers come back for the drawings on cups and bags, orders remembered before they reach the register, and humor that does quiet work. “It breaks the ice, turns down the temperature in uncomfortable moments, and endears our staff to customers.”

The cafe also makes visible barriers that often remain hidden in traditional hiring. Brittney Burkholder, director of supported employment, pointed to online application systems that rely on keyword screening, which can prevent qualified applicants with disabilities from ever being seen by a human reviewer. Rigid scheduling practices, she noted, can create another layer of exclusion, narrowing access for people who could otherwise thrive. Employers often assume inclusive hiring will make their jobs harder. In practice, Burkholder said, it rarely does. Inclusive hiring is simply another way to reach reliable workers who are frequently filtered out before they are ever given a chance.

At Point Perk, learning and employment are intentionally intertwined. Brandon Releford, executive director of education for The Point Arc, described the cafe as a place where employees build communication skills, workplace readiness, and confidence while working real shifts. Experience accumulates in real time. The job itself becomes the classroom. For employers who assume inclusive hiring will slow them down, the model offers a different outcome. When people are supported to learn on the job, reliability and retention tend to follow.

Across all three organizations, the lesson is consistent. Employment that lasts does not begin at the moment of hire. It begins earlier with time, structure and intention. Starfire Council builds alignment before a job starts. Easterseals Redwood designs systems that support people through different seasons of life and service. Point Perk treats work as a place where learning continues on the job.

These models are not fast, and they are not effortless. They require investment, flexibility, and leadership willing to rethink how hiring works. Taken together, they offer a clear response to a labor market defined by shortages, churn, and enforcement-driven disruption.

They are not a workaround to a broken system. They show what it looks like to build something more durable in its place, not by scrambling to replace what was lost, but by creating workplaces that include people who were never fully counted to begin with.