‘We have to create a vision for what we’re building toward’: A foundation CEO speaks to the health of neighborhoods

Becky Payne’s work has focused on supporting projects to improve overall community health and well-being.

In communities across Greater Cincinnati, life spans vary widely. People live to their 90s in the wealthiest neighborhoods, and die in their 60s, on average, in the poorest ones. For generations, some neighborhoods have lacked what they need for their residents to lead healthy lives. Over the last year, Soapbox has examined this disparity, as well as efforts to improve, in the Health Justice in Action series. In this year’s final article, the CEO of a national philanthropy speaks to her work to support change to make our communities more responsive to what people require in order to live long, healthy, thriving lives.

The Rippel Foundation was founded in New Jersey in 1953 following the death of Julius Rippel, who made a fortune through his investment firm. Upon his death, the Foundation was established in the name of his late wife, Fannie. Today, the Foundation supports work across the country, including in Cincinnati, that addresses changing old ways of doing things and funding collaborative efforts to improve overall health and well-being.

Its CEO is Becky Payne, who divides her time between Atlanta and Cincinnati with her husband, a professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s and University of Cincinnati. For 20 years, Payne served in leadership roles at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While there, she led an ambitious plan across dozens of federal agencies to improve the resilience of cities, towns, and neighborhoods following the Covid-19 pandemic. Called the Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience, it lays out 78 recommendations to coordinate government resources to improve health and resiliency in local communities. Under the current federal administration, the plan has disappeared from the CDC’s website, but an archived version of it can be found here.

The plan, and the Rippel Foundation’s work, is organized around improving seven “vital conditions” that shape our daily lives. They include decent housing, good-paying jobs, education, reliable transportation, and importantly, having a say in civic decisions.

Soapbox interviewed Becky Payne about her work and its mission to improve community health. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Why do some communities fail to thrive?

Our communities tend to get fractured and siloed, and the incentive is to stay focused on the thing that any given entity — a government agency, a community-based organization, a private company — on the thing that you can be best at. That works in the business sense, but when you think about our lives and how an individual goes through daily living, it’s the context around things that we all need. Whether it’s education for our children, or for seniors to grow and age in place, or for people to gain skills through trades, or access to health care. Whatever it is, when that is split up and planned for only in siloed ways, you get fractured, disjointed systems that don’t talk to each other.

What can be done about it?

We don’t really incentivize collaboration and working across those boundaries in ways that society needs us to. But we’re seeing more of that as we as we see people and organizations looking to bridge differences and regain touchpoints in communities, identifying with the fact that we all love this place, we’re here together and we share that in common. That is a good starting point. Then we start to find people reconnecting about the things that they are responsible for and how they have touchpoints that can support each other’s aims.

How does this translate into people’s everyday lives?

Health care access is a huge part of it. Prevention versus crisis and being able to maintain health so you don’t have to rely on emergency care services. But also: do people have access to jobs that can support and fulfill basic needs? Do they have humane housing? Do they have transportation to maintain a job? As you get out in more rural areas, we often talk about broadband access, which is so important not just for commerce, but also for education.

READ MORE: Why does one town struggle while its neighbors thrive? The answers date back years

You’ve spoken about the need to lessen our dependency on emergency services. What do you mean by that?

Urgent services are the traditional place we go to invest during a time of crisis. Emergency housing, emergency food vouchers, substance abuse treatment, things that people need when they’re in crisis. Compare that to investments in the vital conditions that we need in order to thrive. Urgent services are necessary and critical to getting people on a momentary stable footing, but no amount of investing in them is going to get people to no longer need those services and get them on a path toward thriving. We have to find ways for leaders and community members to support investing in both, and shifting some investments into vital conditions in order to get people off of the dependency of needing urgent services.

READ MORE: Demands for emergency medical service are stretching the budget of small towns

READ MORE: Living on the edge: Eviction takes a toll on the health of families

How does the Rippel Foundation support communities?

We have the frameworks and tools that are the result of a couple of decades of studying what is needed to help support people to thrive. Through our philanthropy, we have taken all of that research and put it into tools and resources that can be shared with community groups, with organizations, and package it in ways that can be easily understood.

Are there any local examples?

At Cincinnati Children’s, Carley Riley is a researcher and physician who has used the vital conditions to organize a tremendous effort of engaging the community and making sense of health assessment. Over the last year, she’s worked with community members and Gallup to collect data on Hamilton County residents’ experience with each of the vital conditions, as well as their experience of thriving, struggling and suffering. She’s been hosting workshops with community-based organizations across the region to look at that data and then fostering a collective conversation on what do we want to do about that.

Any others nationally?

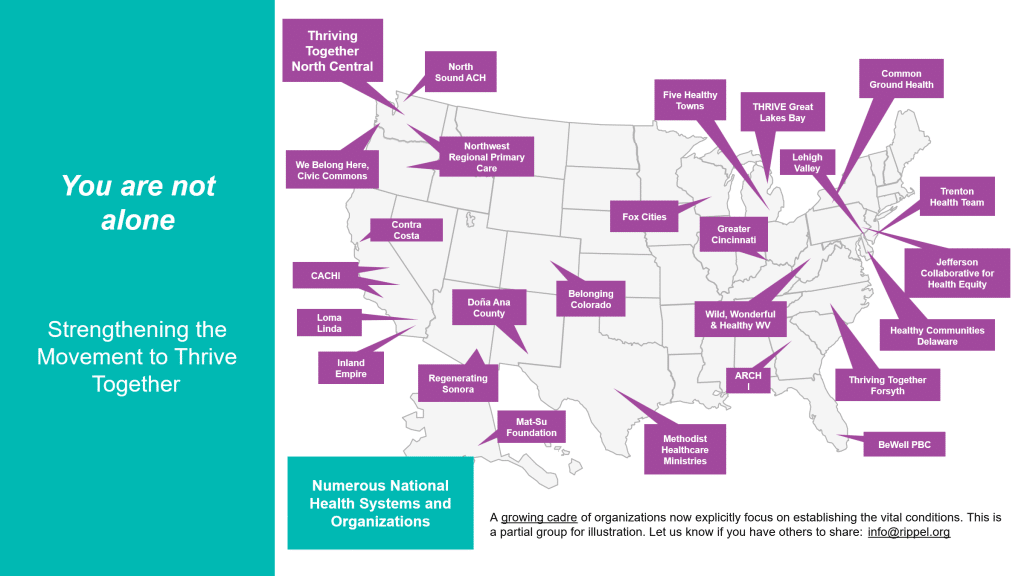

We have a number of states and regions that have been using the vital conditions to channel philanthropic giving. Community foundations in places like the Inland, North Central and North Sound regions of Washington State, and the entire state of Delaware have used this to do their community health improvement planning. Once people are generally exposed to it, we see a rapid desire to share within a region and cultivate conversations, facilitate resident engagement and what we call meaning-making, a dialogue-based exploration of it. Then we see a real conversation among decision makers about what needs to shift and who can commit to that. Philanthropically, we’ve seen new funds established, especially around building belonging and civic muscle, which is one of the seven vital conditions.

Where’s a good place to start?

We have data that shows if you have to choose a place for investment, the best first place to invest is in belonging and civic muscle. Those investments have an outsized impact on the potential for progress on the other vital conditions.

READ MORE: Power to the people: Neighborhoods flex their civic muscle to bring about change

It seems like the social environment today is the antithesis of what you’re working toward.

If you listen to the news, it feels like everybody is divided. It’s actually not true, and we’re finding that in communities across the country. While the national narrative is one thing, it is so powerful to be able to show people there are many more bright spots at a local level, especially when you anchor into people’s love of their place. People love to love where they’re from. They love to talk about it. They love to talk about their hopes and dreams for that future. If we stay there, that is the antidote for these times, and it is the way to cultivate bringing people in off the sidelines.

Aren’t people too divided today to agree on these?

When we get down to the local level and start to see tables being set where community members can come together and sit in dialogue, it’s the antithesis of polarization. It’s the antithesis of ideology. We see resonance for people across the political spectrum, we see a way to overcome division and start to build the muscle to bridge those divides and anchor in the things that we hold in common. If you think about the things that we want to leave for future generations, really think about long-term, decades in duration, then you start to see people actually wildly agree on the things that they want for the future. You get agreement that, yes, I actually want those same things for the future of my family, for the future of my community, and you start to build trust.

How can community leaders help?

Where community leaders come in is creating the outlets for those people who recognize a shared value to spend time together in smaller ways, working on progress toward those goals. Don’t take on the grand experiment of political change all at once, but get them in their shared love of their place and contributing their skills, their assets, their passions, to improving that place. We have to overcome the misguided approach that we can continue to perpetuate the siloing of the resources that are in our communities. We have to have frameworks that are capable of holding the assets of all the different sectors that feed into our communities and require space for meaningful engagement from residents to continue to participate and shape where we’re heading. We have to overcome the division, and we have to create a vision for what we’re building toward, not just what we’re resisting.

This series, Health Justice in Action, is made possible with support from Interact for Health. To learn more about Interact for Health’s commitment to working with communities to advance health justice, please visit here.