Confronting obstacles to implement theory of change

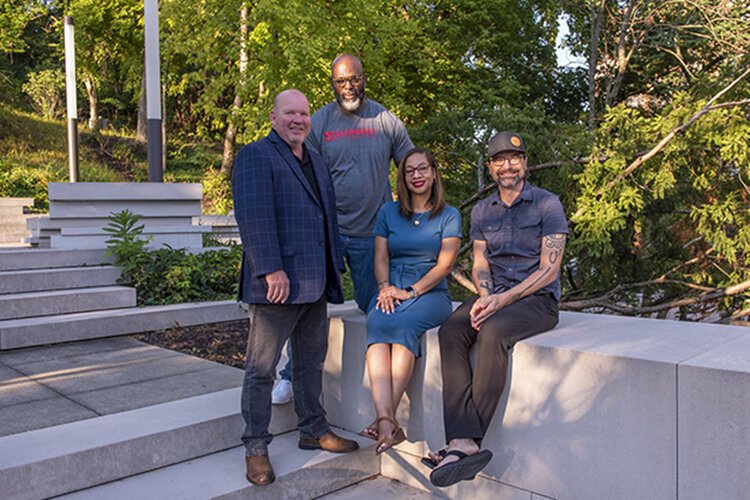

Four local nonprofit leaders speak out on frustrations and hopes for what Cincinnati and Hamilton County can yet become.

Since moving to Cincinnati four years ago, I’ve engaged in the transplant’s favorite parlor game of trying to make sense of the place. Mike Moroski, an outsider himself twenty-five years ago, says he fell in love with the city because he “could wrap his arms around it and maybe do some good.”

Although similar to Mike in her commitment to the civic good, Rickell Howard Smith’s Queen City roots run deep. A fifth-generation Cincinnatian who went east for college and law school, Rickell felt called back to her hometown.

Mike and Rickell, singular though they are, represent familiar types in the Cincinnati story. The transplant who committed himself and never left; the hometown girl who saw the wider world only to return with her talents as an adult.

For this article, I spoke to Mike, Rickell, and two other local nonprofit leaders to understand what drew them to their work and how, obstacles and all, they try to implement their theory of change. These four leaders form a kind of Greek chorus. In their voices, we can hear their frustrations but also their hopes for what Cincinnati and Hamilton County can yet become.

Dramatis Personae:

A boss once told Rickell Howard Smith that she thinks like an architect. And indeed, Rickell pays close attention to how systems interlock. Since returning to Cincinnati in 2006, she’s worked on legal and policy issues for organizations ranging from the Children’s Law Center to the Greater Cincinnati Foundation. Currently, she focuses on police reform in her role as Executive Director of the Center for Social Justice at the Urban League of Greater Southwestern Ohio. She is also a judicial candidate for the Hamilton County Juvenile Court.

Mike Moroski said his best career move was getting fired from teaching at a Catholic school. With his firing—Mike had publicly supported gay marriage—he pivoted into full-time community work and politics. For decades he’s worked on affordable housing and is a member of Cincinnati Public Schools Board of Ed. In 2021, he became Executive Director for the Human Services Chamber of Hamilton County, which he described with Moroskian gusto as “the greatest job in the world.”

Jamie Steele’s life work has revolved around helping those with developmental disabilities. Since 2013, he has served as Executive Director of Ohio Valley Residential Services. The organization has 200 employees and owns 22 homes and apartments in Hamilton County in which it cares for and houses 155 individuals with Intellectual Developmental Disabilities.

Education and the arts—these are Damian Hoskins’ pillars. After a thirteen-year career as a classroom teacher, Damian has worked as a VP at ArtsWave and was part of a team from KnowledgeWorks that helped spearhead the Preschool Promise. In 2021, he joined Elementz and is its Executive Director. Damian’s one of those rare individuals who could make a discussion of insurance bylaws sound compelling. He teaches a class on Hip Hop studies at the College-Conservatory of Music.

I conducted these conversations over Zoom and once by phone when one member of the Greek chorus had to pick his car up from the mechanic. Their words are their own, though in places I’ve lightly edited for clarity and length.

Alex: How would you explain your career path?

Rickell: My career path has been one where I take one step and then the second step is sort of pulled along in order to move the work forward. When I graduated from law school, I knew that I was interested in doing social justice work and also that I needed actual training to be a lawyer. So I started out at Legal Aid. It was a very challenging job because you have a client or a family that comes in for one issue. And when you talk to them, you realize that every single part of their life is affected. So, if you resolve one issue, then you still have this whack-a-mole problem.

Mike: Circuitous at best. I was raised in Atlanta, kind of a punk kid with a chip on my shoulder. I still am. I just figured out a way to get paid to have a chip on my shoulder.

Jamie: I grew up in a household of six siblings. My brother Andy and I were at the end of the line, numbers five and six, so we got real close. Andy had a disability and was involved in services, and I tagged along. As a kid, when I was thirteen, I started to volunteer with people with disabilities. That was the call for me.

Damian: I’ve been in several different places occupationally, but they’ve all had a similar trajectory. I have either been in education or in the arts. It’s just been one of those two places.

Rickell: Being a black woman doing this work, there’s an added layer of challenges. Cincinnati has changed a lot. The rooms have become more diverse. But there were times where I was litigating cases in federal court when I was the only black person in the courtroom. And there are challenges that come along with that too. Not only is the world challenging, but it’s challenging based on your personal identity and how people receive or are receptive to your message based on who you are.

Mike: I think we have a couple of super profound experiences in our lives if we’re lucky. I’ve had maybe two or three, and this was the first. I was eighteen and I knew then that it was a profound experience. I didn’t maybe know why; I just knew that it was. So I’m outside smoking a cigarette at this rehab facility I had to go to and I’m talking to this young black kid from south of Atlanta. And I lived north of Atlanta, and he’s asking me why I was there and I’m telling him the drugs I did and all the tough shit I was into. And mind you, I live on a golf course like every other tough kid. Then he asked me where I went to school, and I said, Marist, which is a good school. He proceeded to berate me. I mean, he went after me. Like, “What is your problem? How can you go to school like that and then throw away all this opportunity?” I had no idea what he was talking about. And then he started asking me, “Have you ever had to hold your friend’s hand because he got shot? Have you ever had to go to Grady Hospital and see your uncle die because he got shot in a drug deal?” I didn’t know what I said that was wrong. All I knew is that I felt bad. And then and there, literally, I decided to quit fucking around.

Alex: What are the primary issues facing your organization?

Jamie: We’re always constantly having to fight for funding. We are so unlike the marketplace. As companies need to raise wages, they often raise the price for their products. We can’t raise the cost of the products. The pandemic, moreover, deeply affected human services. We’re having a hard time recruiting staff, paying staff a good living wage, and training them to provide a professional service to individuals. In the meantime, all the other stuff that got us into the field—poverty, homelessness, disability, mental illness—is still there and growing. So you can see the conundrum.

Damian: The organization faces a few issues and then the people that we serve face independent issues that I hope that Elementz helps to address. We are probably one of three or four black-led arts and cultural organizations in the region. So those numbers are disproportionately small. And as such, historically, and given the fact that we’re an organization focused on Hip Hop culture, there was the perception that we were either a charity or that the work was disposable. But we are not a charity. Hip Hop culture is a multibillion-dollar industry. Full stop. We’re not operating from a deficit model where you need resources for the poor black kids in the community. All of these kids bring an asset to the table. They are culturally curious. They have a whole lot of creative skills.

One of the difficult things for me and my staff is making sure that we’re highlighting the assets more than we’re focusing on the deficits. Do our young people come from challenged communities in the urban core? For the most part, yeah. But we also look at it like we look at Hip Hop. Where you come from doesn’t determine where you’re going.

Mike: The thing that keeps me up at night with this job, it’s the thing that’s kept me up at night with every job. Sadly, because it hasn’t changed. It’s difficult for me to see a broader, larger political will to make the substantive changes that need to happen for people in our society who need it, namely for poor people and black people.

Rickell: The Center for Social Justice’s original focus was the region. And when I came in, even though I’ve lived here most of my life, I discovered there are forty-two law enforcement agencies with jurisdiction just in the county. As we started talking directly to police chiefs and communities in Hamilton County, we found out how vastly different these agencies operate that are sitting right next to each other. From St. Bernard to Elmwood Place, you’re going to get a totally different police response. That makes advocating for any reform very difficult when you can literally drive Vine Street from downtown all the way up through Butler County and pass through eight different municipalities, each with different capabilities and philosophies on how they police their neighborhoods.

One of the biggest challenges was even figuring out what everyone is doing. It’s hard to say that you want to reform something until you know what your baseline is. So, we spent a good amount of time trying to meet as many police chiefs and talk to as many community members that were living in these municipalities and building relationships and credibility across the board.

Our second challenge became getting enough interest from residents to stand up and say, “Hey, we want to see change in our community.” I don’t mean that in a judgmental way at all. Because the truth of the matter is the same residents that will face inequities will be disproportionately impacted by bad policing practices. And you’re asking them to step up and say they’re going to dedicate their time and their talent to this effort. The landscape is so huge that community push is really going to be needed in order to change anything. I think of the community as my client, and I can’t move and make decisions ahead of what the community wants.

Alex: What’s your theory of change?

Damian: As an organization, we have a particular impact objective that informs our theory of change. And that impact objective is based on something that I call the exposure quotient. Essentially, a child enters into the world based on the things that they’ve been exposed to, which informs what they desire, which informs their intelligence. For adults, our challenge is to ensure that the exposure quotient is something that is rich and meaningful. Otherwise, especially in the urban core, kids can be exposed to just about anything and those things can be detrimental. So that’s what really influences and informs our theory of change.

A part of what we are attempting to do is systemic. The system is created, it’s designed this way. It’s not broken. It’s designed to benefit certain people and not benefit others. The change for us is to not focus so much on the system but on how we react to be conditioned to the circumstances. We may not be able to retroactively go back 400 years and re-frame the system. But we do know that there are things that we can do that provide us with agency right now. And in shifting those behaviors, we’ll inform our intelligences and inform how we show up in the world.

Mike: This isn’t Pollyanna. If there’s a coalition of nonprofit agencies walking in lockstep and singing from the same hymnal, then those who are holding the purse strings will be more amenable to funding.

Rickell: My trifecta for systems change work: 1) Having strong community organizing. 2) Having a strong policy advocacy strategy. 3) Having the data to support the change you’re looking for. The piece that is always a curve ball is the policy advocacy strategy. Because you have to pivot that around who your elected officials are. The data piece is so important because data gives the policymakers the courage to do what they know they need to in the first place.

Jamie: In the disability field, we see the person first and the disability second. That has become a sole mission of agencies such as mine. And getting people—our staff, our clients, our clients’ families, government officials—to understand that we are here to help support the people that find themselves in a situation that’s beyond their control or even if it is in their control to help them out of that. It is mission driven. Why do we do what we do? How do we make a difference? How do we help humans succeed in life as best they can?

Alex: If you had a magic wand or if money were no object, what would you do to tackle the challenges your organization faces?

Jamie: I hate to repeat myself. I would enhance mission.

Rickell: First, I would put money in the hands of actual people and individual families that have been historically disenfranchised. As many people as I can give a better start to. Second, I’d be a philanthropist that would focus solely on systemic change work at the community, city, and state level.

Damian: Ultimately, we’d make sure we had an endowment. And we’d frame Elementz the same way that other sustaining impact arts organizations have been able to frame themselves. Elementz has been around for 20 years. Hip Hop culture is only 50 years old. But the symphony and the art museum and the ballet, those guys have a 150-year head start, which is why they are institutions.

Mike: I would ensure enough housing existed for EVERYONE and that every public school was funded constitutionally.

Alex: What will frustrate you if you’re still having to talk about five years from now?

Rickell: It would make me sad if we were still talking about the importance of collecting data.

Mike: Affordable housing and rampant racism. Which I sadly know I will still be talking about five years from now because the will does not seem to be there to authentically do something REAL about either.

Jamie: If our organization doesn’t grow, that’s going to hurt people with disabilities who need our services. And we can’t grow if we don’t have the staff and the resources.

Damian: If we in the Cincinnati area are still talking about the fact that black-led organizations or organizations that are specific to BIPOC people are less than five per cent of the art and culture that is to be shared with the public, if we’re still talking those low numbers, I’m going to be really pissed off.

Alex: What will make you heartened if you’re no longer having to talk about in five years?

Jamie: The thing that would hearten me in five years is if individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities would get the residential support that is needed and wanted. This could be 24-hour supervised support. Or five hours, ten hours, or no in-home staff but rather their needs are met by remote support technology.

Mike: I would love if we were all talking about how to support public schools for real and how to house people for real.

Rickell: I would be ecstatic if we had some national standards around police training, evaluation, and accountability that were developed by communities across the country. From a practical standpoint, I would be ecstatic if we no longer saw people being killed or had to experience or hear of police interactions that ended in death.

Damian: Conversely, if we get to a stage where those numbers are equal or balanced, I would be super excited because that would reflect greater collaborations. There will have been greater equity and funding. That would be the most exciting thing for us to be able to talk about.

There are so many young people, particularly artists, who look at Cincinnati, look at the lack of diversity and say, “I’m not staying. I’m going somewhere where there is a greater reflection of diversity and culture, and in the arts in particular.” And so it’s good business for Cincinnati to have an arts and culture scene that is a greater reflection of the people that we serve.

Five years from now, I’ll be fifty-three. My kids then are in their mid-20s. My hope is that they get to see the Cincinnati that I wanted to see at eighteen.