The Philanthropic City: Sharing the wealth to build strong communities

Philanthropists have built and sustained this city and many others, funding the arts, improving the quality of life, and expanding health care and education. Can they respond to changing community needs?

Cities are engines of our local and national economies, and centers of creativity, culture, and entertainment. But they are under more pressure than ever. This is the latest in a monthly series, The Case for Cities, that looks at how Cincinnati and similar cities can grow by becoming places of choice, as well as models of social justice.

By all accounts, Charles H. Dater was a frugal man.

Although he was the inheritor of a family business, Charles lived his years in a modest, three-bedroom ranch on Ferguson Avenue in Westwood. When he and his wife dined out, it was often at Frisch’s. He drove his cars until they wore out. One of them was a Dodge Aries K-car, a low-budget economy car that could be bought new for about $7,000 in the ’80s.

He managed the family’s investments and real estate adroitly, and by the time he was in his 70s, he had amassed what can only be called a small fortune. The Daters had no children, and when Charles was planning for his estate, the idea of a foundation came up, an idea that appealed to him. In 1985, he established the Charles H. Dater Foundation, and in its first year, the Foundation made 13 grants totaling the modest sum of $9,500.

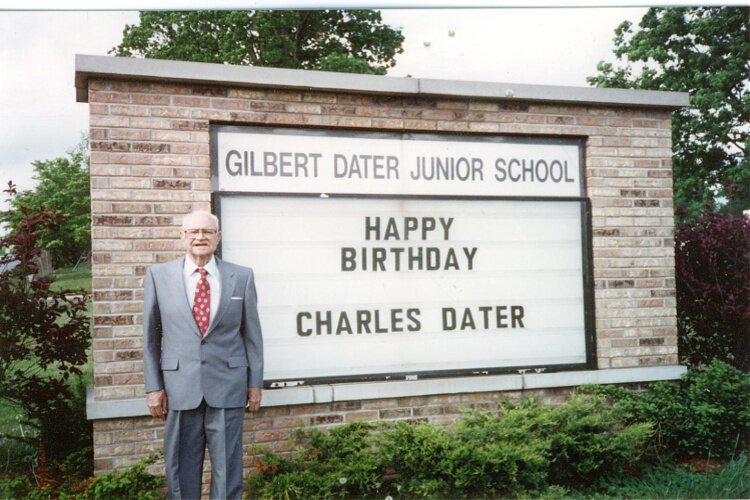

Dater died in 1993 at the age of 81. The Foundation lives on, and now gives away about $5 million a year. Since it was started, the Dater Foundation has made more than $55 million in grants, with a mission to support organizations that benefit youth. Two West Side schools bear the Dater name: Gilbert A. Dater High School (named after his grandfather); and Dater Montessori, an elementary school.

His name on the schools are about the only public recognition of the impact of the Dater Foundation, as Charles is said to have also been a humble person who, when he was alive, preferred to give anonymously, and in any event, didn’t seek recognition for his charity.

“We’re kind of a quiet foundation,” says Roger Ruhl, a vice president and board member. “We tell grant recipients just go do good work and serve your constituents.”

Dater’s vision, generosity, and legacy has benefited thousands of Cincinnati kids. It has funded expansions at Children’s Hospital, a reading room at the Westwood branch library, programs for underserved youth at the Clippard YMCA, programs at the Down Syndrome Association of Greater Cincinnati, and a lot more.

It’s a classic, Cincinnati story: a thrifty West Side family saved its pennies for generations and shared its wealth with its hometown. But The Dater Foundation is not unique in its generosity.

Over the decades, local foundations and other philanthropic organizations have made investments that have built and sustained this city and many others. They’ve built institutions, funded the arts, improved the quality of life, expanded health care and education, and supported and endowed efforts to foster social justice.

Cincinnati’s vibrant and diverse arts scene wouldn’t be the same without the significant contributions from foundations funded by people named Corbett, Nippert, Budig, Rosenthal and others. The Procters, Gambles and their heirs have donated millions to improve health care and other causes. Jacob Schmidlapp funded low-income housing and the arts with his banking wealth. First-generation American Manuel Mayerson put a real estate fortune to work supporting Cincinnati’s Jewish organizations, education, and impoverished children. Murray Seasongood was a lawyer and politician who pushed for government reform in Cincinnati, and set up a foundation devoted to good government. Carol Ann and Ralph V. Haile, Jr. had an eye on opportunities for improvements they could make to the communities around them.

(Full disclosure: The Murray and Agnes Seasongood Good Government Foundation, as well as the Carol Ann and Ralph V. Haile,Jr. Foundation support Soapbox Cincinnati.)

And corporations and just regular people donate tens of millions every year to the United Way of Greater Cincinnati, which supports dozens of local social service organizations.

“We invest in the things that are important in this city,” says Kathy Merchant, who was president and CEO of the Greater Cincinnati Foundation for 18 years, until her retirement in 2015.

Some see the challenge for philanthropies today as responding to the changing needs of a society in which the wealth gap between the rich, the poor, and the just-getting-by has grown rapidly, and where decades of racial inequities have come to the surface.

Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, one of the largest foundations in the country, with an endowment of $16 billion, has written about this. “For all the good philanthropy has accomplished – for all the generous acts of charity it has supported – it is no secret that the enterprise is both a product and a beneficiary of a system that needs reform,” he wrote in “From Generosity to Justice: a New Gospel of Wealth.”

Philanthropies are beginning to respond to calls for systemic reform.

Greater Cincinnati Foundation is this region’s largest community foundation, giving away more than $120 million in 2020 alone. Started in 1963, the Foundation’s focus and strategies have evolved, as it focuses today on advancing racial equity and opportunity. One of its programs is Racial Equity Matters, a program funded by bi3, Bethesda, Inc.’s grantmaking initiative. As part of that, it’s made the diversity and equity training program that delves into the root causes of racism available for free to thousands people since 2019.

“Making sure you change as community needs change is really important,” Merchant says.

Matt Butler and his wife, Rebekah Gensler, assessed community needs to figure out how to have the most impact when they started one of the region’s newest philanthropies, Devou Good Foundation, in 2014.

They had founded an e-commerce business, Signature Hardware, with $10,000 in savings in 1999. Based in Erlanger, it grew to become one of the largest, direct-to-consumer decorative hardware companies in the country, selling freestanding bathtubs, decorative sinks and vanities, door hardware, floor registers, shower rods, faucets and the like. By the time they sold the business, it had grown to 220 employees and 400,000 square feet of space.

Only in their mid-40s, the couple decided to use their money and time to give back.

“We’ve always given back, but we were busy raising kids and growing the business,” Butler says. “Our giving was more passive, sending checks to other nonprofits.”

With the creation of Devou Good, they’ve devoted themselves full-time to making a difference.

The first step was figuring out where they could have the most impact. They began meeting with people and organizations to see where the needs were. Child care and transportation kept coming up. Lots of not-for-profits, such as the Dater Foundation, already work on children’s issues. But there wasn’t a great deal of activity around “active transportation,” or non-automobile transportation.

In doing his research. Butler found that 20 percent of households in the region lack access to a car. When you figure in those who are too old to drive, and those who aren’t old enough, “There’s a lot of nondrivers in this area,” Butler says. “It seems like they’ve been overlooked. They don’t always have a voice at the table when decisions are being made.”

“Active transportation,” meaning essentially any means of getting around besides in cars, became Devou Good’s primary focus. It funds infrastructure projects in Hamilton, Kenton, Campbell and Boone counties designed to make walking and bicycling safer, such as bike paths, lanes, trails, and bridges; off-road trails that can be used to connect neighborhoods; infrastructure to slow traffic in neighborhoods; creating safe, walkable and bikable neighborhoods; bike racks, bike parking, bike repair stations and bike storage.

It’s funded a thousand bike racks in Cincinnati, 500 in Covington, and 100 in Newport and other cities in Campbell County. It helped form VisionZeroNKY, a task force to eliminate all fatalities and severe injuries from automobile traffic. For the past few years, it has funded half the operating expenses of Tri-State Trails, a community advocacy group working to expand the region’s trail and bike path network. It funded a protected bike lane on Clifton Avenue, safely connecting residential neighborhoods with the University of Cincinnati.

When COVID emerged and restaurants in downtown, Over-the-Rhine and Northern Kentucky resorted to outdoor dining to stay in business, Devou Good brought the idea of “streateries” to the public – outdoor dining areas on sidewalks and streets that were at once attractive and protected from traffic. The foundation contributed seed funding, which, when combined with funding from other foundations and the city of Cincinnati, supported 85 businesses with streateries. The funds were also used to build raised crosswalks on Vine and Main streets in OTR, slowing traffic along those high-traffic corridors that are often packed with pedestrians.

The foundation invests in more than infrastructure. It will work with community councils to inform them about what can be done to calm traffic in their neighborhoods and reduce speeding and reckless driving. At times, they advocate for public policies.

Devou Good lobbied Cincinnati Police to make OTR a “no-chase zone,” meaning no vehicle chases by police. This came shortly after a chase in 2020 by Cincinnati police ended across the river in Newport with a crash that killed a couple in their 80s who were dining outdoors. Cincinnati Police in March did amend its chase policy, permitting chases only if suspects are believed to have committed violent felonies.

“We look at how can we have the greatest impact,” Butler says. “If there’s areas where policy is in conflict with our stated goals, we need to speak up. It’s important to speak up for people who don’t have a voice.”

Butler neatly sums up his overall philosophy and that of many philanthropists who have preceded him: “It’s important that people who have been successful like ourselves give back, pay it forward, and try to raise up as many other people as we can.”

You can read earlier articles in The Case for Cities series here.

You can view and listen to The Case for Cities conversation series here.

The Case for Cities: Cities of Choice are Cities of Justice series is a partnership between UC School of Planning and Soapbox Cincinnati, made possible with support from The Carol Ann and Ralph V. Haile, Jr. Foundation.