City of Opportunity: Cities shaped one man’s journey from growing up poor and Black to prosperity

The experiences of urban life played a role in the groundbreaking career of Ed Rigaud in business, entrepreneurship, and sports.

Cities are engines of our local and national economies, and centers of creativity, culture, and entertainment. But they are under more pressure than ever. This is the latest in a monthly series, The Case for Cities, that looks at how Cincinnati and similar cities can grow by becoming places of choice, as well as models of social justice.

—

“I was fortunate to grow up poor and Black in New Orleans,” says Ed Rigaud. Growing up in that city, and then beginning his professional life in Cincinnati, led to a groundbreaking career in business, entrepreneurship, real estate, and then as one of the first minority owners of Major League Baseball’s oldest team. He also shares his experience with young entrepreneurs and not-for-profits through his mentorship and service on numerous boards.

Here are excerpts from a conversation about his life, opportunity, and the impact of cities.

Rigaud grew up the son of a career Army father and a mother who worked at home as a seamstress and took care of the children. From an early age, he was drawn to the creative side.

I can remember as a three- or four-year-old, when my mother was teaching sewing class in one part of the house, I was in another part drawing and I would run in with a new drawing and show it to her. She was really busy but took the time out, and said, ‘Oh, son, that’s beautiful. Go make Mommy another one.’ I loved to read. I was focused on more intellectual things all the way through the Catholic nuns who taught me in elementary school, the Catholic priests who taught me in high school. I had asthma so I didn’t play sports. At one point I was so ill with asthma, I was in an oxygen tent at home for three months. I had plenty time on my hands and we had a set of encyclopedias and I decided I’m going to read them, and I read from A to Z in the encyclopedia.

He was exposed to other cultures and to a desire to create a better life.

I had some occasions to experience the segregation that was going on, but I wasn’t really cognizant of it. The Seventh Ward in New Orleans where I grew up was predominantly Black. The stores on most corners in that neighborhood were not black owned or run. They were Italians and Greeks. I thought that was normal. But the Black people in that neighborhood all had aspirations, educational aspirations, and career aspirations, and some of them were doctors and lawyers. So it was kind of like Harlem would have been, where you got to see very successful people and you got to see really indigent people but they all seemed to have a zest and a desire to succeed. So I was fortunate because I got to see that side, and I got to contrast it with Cincinnati life, and I feel I’ve had a richer experience than I otherwise would have had.

New Orleans in the ‘40s and ‘50s was a segregated society and racism could be blatant.

We knew where we weren’t allowed to go. I mean, it’s not like we never saw a white person, but when we did it was strange. One time I remember, my dad was in Korea, fighting, and my mother was taking care of the kids. I must have been seven or eight. And she said Come on, kids we’re going to hop on the bus and we’re gonna have a picnic at City Park. And we got on the bus, sat in the back with the “colored only” signs in front of us. We get to city park, and we found a picnic bench and we started laying out our food. It was really a beautiful day. Now along comes this policeman on a big horse and he takes the horse right over to our table. And he yells at us and calls us the worst things in the book. I can still vividly remember that horse and this big policeman, and I wanted to fight him. I wanted to protect my mother. I couldn’t figure out why he was doing this. So my mother collected our stuff; it started drizzling, and we stood in the rain waiting for the bus to go back home.

His plan was to become an architect, but that dream ran into the realities of the South in the early ‘60s.

Because of the art influence I had, and I loved math and science, I wanted to be an architect. I finished third in my class at Saint Augustine High School. So I applied to LSU which, had a pretty good school in architecture, engineering and related studies. I got a letter back, which I still have, that basically said, ‘We’re sorry, but our policies won’t allow you on our campus at this time.’

What did they mean by that?

There was only one interpretation. I was a strong academic student with everything else good.

What did you do?

I had a full scholarship to Xavier University in New Orleans. They didn’t have architecture or anything related, but they had chemistry and I was really good at chemistry. So I went to Xavier and became a chemist.

A chemistry degree led to a job opportunity in Cincinnati at Procter & Gamble, where the company was developing a new kind of crispy snack that eventually became Pringles.

We needed a potato chip type snack that had a much better package where the chips wouldn’t get crushed. I was named the technical brand manager and took it from that early concept stage all the way to test market and to a national launch.

Procter & Gamble, where Rigaud worked for 36 years, was an education unto itself, and opened doors.

It was almost everything. I give a lot of credit to my mother and to the Catholic schools I went to, but P&G taught me everything else. I learned teamwork was a big, big piece, and how to motivate people. I remember introducing a concept I liked called HOFF, which stands for honesty, openness, fairness, and fun. That’s how I tried to run the teams I had. I was able to kind of name where I wanted to go in the company. So I moved from R&D after about 20 years into marketing and general management, which at the time was not an easy move to make, but I had a boss who said ‘Ed, you can do anything you want.’

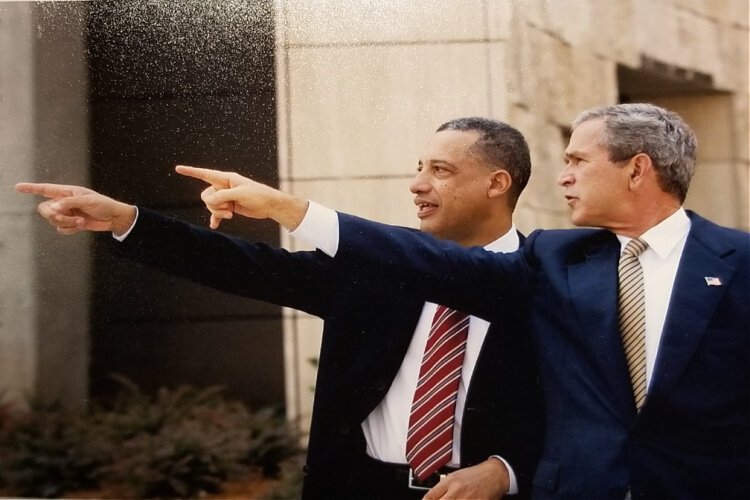

In 2001, after a series of deaths of black men at the hands of police, some institutional changes began in Cincinnati. One was the creation of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, fulfilling an idea that had been born years earlier. Rigaud was asked to lead it as an executive on loan from P&G.

It was supposed to be a three-year stint and it turned out to be six and then P&G said, ‘that’s it.’ I stayed another three years, and in that nine-year period, I got a taste of how to utilize all the skills that I developed at P&G in a more independent, entrepreneurial context that was not for profit. That made me think maybe I can do this in real world as an entrepreneur.

After retiring from P&G, Rigaud went into business for himself, buying an automotive supplier, EnovaPremier, which counts Toyota and other automakers as its customers.

I was surprised at how sophisticated this business was. My partner and I bought the assets of this company, which was struggling, and we turned it around. It took three years to negotiate the sale, but once we acquired it, we ran it like a P&G operation.

The connections made in the city — business, personal, and intellectual — were critical to his success.

I don’t know what it’s like to not be in an urban setting. Everything you need is there. Everything you need to succeed is in the city.

He refers to the concept of the “whole brain,” and how cities can provide experiences to light up all four quadrants of the brain and improve well-being.

I always think about how the brain works and there’s four functions you’re exposed to that develop the whole brain. Creativity, problem solving, leadership, and compassion. There’s a plethora of opportunities to develop each of those in the city all the way from early childhood to adulthood. You’re exposed to stimuli in all those quadrants of the brain.

Opportunity knocked again when the Cincinnati Reds owner sought investors, making Rigaud and his partners the first minority owners of the team.

It’s part of a bigger scheme and objective in my life. I have this guiding freedom pyramid that I created when I was at the Freedom Center, and it’s at the top of the pyramid to have empowerment and self-actualization. It’s the best kind of freedom, which includes economic empowerment and inclusion. So when Bob Castellini came to me and Ross Love and asked if we wanted to take part in this merger I said, yes, absolutely. Because it fits that model of inclusion where if we can get everyone the opportunity to go as far as they can go, we’re going to have a better society. I’m not a big baseball nut. I mean, I enjoy it, but the joy of being a part of it has been great.

As a successful entrepreneur, real estate developer, and executive, Rigaud gives back to young entrepreneurs, both as the current chair of the Chamber’s Minority Business Accelerator, and through his own personal mentorship.

There’s two aspects to that. One is opening the doors for folks who haven’t had an opportunity to invest in money-making opportunities that have been closed to them in fields like commercial real estate. And that’s happened. We’ve opened the doors to a significant degree, including having some ownership and leadership in those ventures. The other is helping African Americans primarily, but also women and Hispanics to have a higher success rate as entrepreneurs. We have a disproportionate number of entrepreneurs in those affected populations but also a disproportionately high failure rate.

After such an impressive career, what’s next?

So at 79, I’m not done. I’ve got to get this thing so it’s moving on its own. And part of that are my friends in the Commercial Club and the Commonwealth Club opening their arms to folks that they wouldn’t normally even know. That’s actually happening. I don’t mind being the first or nearly the first to do something, but that’s not what pleases me. What pleases me is when it opens doors.

You can read earlier articles in The Case for Cities series here.

You can view and listen to The Case for Cities conversation series here.

The Case for Cities: Cities of Choice are Cities of Justice series is a partnership between UC School of Planning and Soapbox Cincinnati, made possible with support from The Carol Ann and Ralph V. Haile, Jr. Foundation.