IKRON goes beyond mental health treatment, offering community, classes, and assistance with job help

The organization — which has been around for more than 50 years — partners with other providers in the region to help people struggling get back on their feet.

Picture a Funnel

David Perry first came to IKRON three years ago at his doctor’s recommendation. The problem was not medical exactly so much as financial: David’s benefits would no longer cover his prescription for Abilify, an anti-psychotic medication that out of pocket would cost roughly $1,000 per month.

David, who suffers from bipolar disorder and anxiety, could not possibly afford the drug on his hourly-wage income. Without it, though, he would struggle to maintain both his stability and independence. IKRON, a community mental health organization founded in 1969, was able to partner with local health centers and state pharmacies that serve the indigent to offset the medication’s exorbitant price tag.

Each year approximately 1,400 individuals use IKRON’s services. Like David, many of them come to the organization for one reason but continue for others. This June, what brought him back was employment support. Now 60, David had left a job he was unhappy with. Cheryl Krummen, IKRON’s placement coordinator, helped David update his resume and vet possible jobs that would be a good fit.

“IKRON gives me the capability to search for jobs,” David says. “They don’t get you the job. They help you find the job.”

It is very much a tag team effort. Both within IKRON, and also with other agencies. Indeed, at the same time Cheryl was coaching David, Amy Stullenberger, a vocational rehabilitation coordinator in partnership with Opportunities for Ohioans with Disabilities (OOD), was working to ensure his eligibility for state- and county-level vocational support. She was also applying to SORTA for a monthly bus pass that David, who had no car, could use until he received his first paycheck.

To an outsider, the often elaborate routes by which Ohio’s mental health and addiction service providers operate and coordinate care can be dizzying. It’s an acronym soup not for the faint of heart. One might be handed a business card and not know what organization the person is with. (Does this vocational counselor work for OOD or an outfit called Pathways 26? And is there a Pathways 25?)

For the uninitiated, it can be helpful to think in terms of a funnel. The funnel’s mouth is OOD, a state agency that provides oversight and contracts with partner organizations. This partnership is what allows Amy Stullenberger to work with referred individuals to help them identify their job interests and coordinate their care with a local provider.

IKRON, a local provider, is the narrow end of the funnel and, thus, what leads David Perry to be seated beside placement coordinator Cheryl Krummen’s desk.

A Name Written in Scrabble Tiles

Located on a downhill slope of Vine Street in a former national brewery union hall across from Inwood Park, IKRON, with its understated signage, is easy to miss. The interior of the building, like the organization’s name (more on that in a moment), has an improvisational air. The ground floor is a mash-up. Several IKRON offshoots run programming, including a small gym (The Mighty Vine Wellness Center), a 24-hour counseling hotline (The WARMLINE), and, less obviously, a florist. There’s also a cafeteria, where IKRON students can get free lunch and coffee, the latter accessible along the curved, wooden bar once used by brewery workers.

The second and third floors contain counselor’s offices; a computer classroom; the Health Resource Center; and a large open space that, when not hosting group sessions, doubles as a yoga studio.

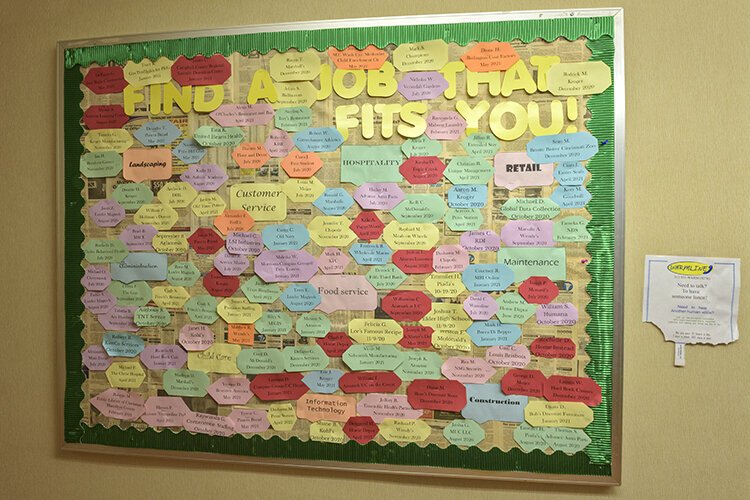

The building’s bathrooms are clean and its stairways hard to find. Along the walls, corkboards advertise both resources — The Substance Use Recovery Group, The Men’s Group, Alcoholic Anonymous meetings each Friday at 2 p.m. — and student achievements, like the board showcasing the names of those who’ve recently landed jobs.

It’s hard to imagine a mental health service agency that feels less institutional than IKRON. Even Executive Director Randy Strunk’s office, with its wood-paneling and ever-expanding shrine to Elvis Pressley, seems better suited as the basement rec room stage set to Wayne’s World.

This familial atmosphere is by design.

“We bring our building to them,” Director of Programming Melissa Harmeling says, referring to IKRON’s students.

On principle, those whom IKRON serves are not called “patients” or “clients,” but “students” or “individuals.”

“How you can tell an individual we serve versus the staff is the way we dress,” says Director of Employment Services Darla Menz. “Outside of that, we are equal, and the same.”

Each year, IKRON typically receives referrals from as many as sixty different sources, and 30 to 40% of its students will have dual diagnoses involving mental health and addiction.

The need for IKRON’s services shows no sign of abating. It has added forty full-time staff positions in the last fifteen years. And the staff, for the most part, chooses to stay.

And what about the name? IKRON didn’t start as an acronym, although it became one. Its board, determined to avoid stigmatizing associations with rehabilitation or addiction, came up with IKRON by moving around Scrabble tiles. Only later did it become acronymized: Integration of Knowledge and Resources for Occupational Needs.

Supported Employment

If IKRON evolved to become a mental health services provider with wrap-around services, its origins lie in vocational rehabilitation.

Each morning Jen Tittermary, who’s worked at IKRON for fifteen years, leads the Supported Employment Group. On one particular day, eight individuals attended, ranging in age from their 20s to 40s.

Jen, who has a calm, unhurried voice, led a session to reinforce best practices at each stage of a job search. The first agenda point: sharing job postings.

American Heritage Tours was hiring tour guides and customer service reps. An upcoming job fair with thirty employers, including Kroger, Cintas, the Urban League, Hard Rock Casino, and Chipotle, among others, would be held at the Sharonville Convention Center. One student new to the area asked where Sharonville was, which led to a discussion of how to reach it.

“That would be Zone 2 if you took the bus,” Jen says.

Students, meanwhile, chimed in with news of job postings. The White Castle on Reading and Taft was hiring. Jen mentioned that White Castle was known for offering good benefits, which another student confirmed.

Jen prevailed upon a student who had just gotten hired to share his good news. He was starting at the Goodwill Donation Center; orientation was the following week. The other students clapped for him and one told a story she’d read about someone buying a painting from Goodwill and finding three diamond earrings hidden in the back of the frame.

Like any savvy instructor attempting to impart useful information, Jen made it fun. This was not a lecture delivered from a podium. Everyone sat in desk chairs in a public-health-friendly circle.

Thanks to the game-style format which Jen led them through, even the quieter students participated. Questions included what to wear and not wear to an interview, whether a cover letter should always be included with any application, questions to ask at an interview, questions not to ask, how early to arrive, what to write in a thank-you letter.

Other questions were designed to familiarize students with IKRON services available to them as well as to educate them about their rights. What couldn’t employers legally ask in an interview? Could an employer ask if they had a criminal record? What was the state minimum wage?

None of the students, hidden treasure notwithstanding, would be getting rich off whatever job they would land. But IKRON’s goal, as Strunk notes, is not just to stabilize individuals but to “move more people towards independence.” A job that a student enjoys improves morale.

What This Building is About

If IKRON strives to help its students find work to achieve greater independence, it balances this goal with its commitment to treat each individual like an individual. And in the past six months, their job development team has averaged 19 job placements a month.

What IKRON does not do is force students to find work before they’re ready.

As Janelle Tumbleson, another vocational rehabilitation coordinator in partnership with Opportunities for Ohioans with Disabilities, explains, “Sometimes employment isn’t the individual’s priority. And so you can interrupt services or put them on hold while they focus on housing or their recovery … Because that’s going to impact the success of their employment.”

Consider Charles Jones, who’s sixty-seven and speaks with the arresting directness of a man trying to learn from his life. His voice is analytical and gentle, but he doesn’t suppress his anguish.

“I [had] two children in the past four years. And I didn’t know how to deal with it. I started drinking and it just consumed me,” he says.

“I made a call [to a friend] one day and I was so screwed up that I couldn’t talk,” he continues. “I was crying. I was sobbing. I was trying to explain what was going on with me, and they kept me on the phone, trying to reassure me that everything was going to be all right, asking me questions like ‘Are you trying to hurt yourself?’ ‘Are you thinking about hurting yourself?’”

That day the police, whom Charles’ friend had called, took him to a psychiatric hospital. From there, Charles contacted IKRON, which he knew about from his younger brother, who had used its services six years ago to help combat a drug addiction.

“I was at a very low point in my life. Family issues. And dealing with the alcoholism. It was too much … [IKRON] provided me with the services they had to offer,” he says. “I guess I’ve been here close to a year now. It hasn’t all been peaches and cream since I got into the organization. I’m still sick. It’s like going to the hospital. You got to the hospital sick. That don’t mean you’re instantly cured because you walked through the door.”

The conversation with Charles took place in a conference room. On another wood-paneled wall hung a framed poster of the International Union of United Brewery, Flour, Cereal, Soft Drink & Distillery Workers of America, an emblem of comity featuring an American and Canadian flag, two sets of hands shaking, and an exhortation for “working men of all countries to unite.” Down the hall, a group of students was doing yoga.

“Sometimes your condition can have you so isolated that you want to try it by yourself. I’ve tried that. But it wasn’t working … and it got so bad that I couldn’t carry on a conversation without bursting into tears and being incoherent,” he says.

“I’m 67 years old. I’ve been doing this for a while. I need a whole revamping. It’s a lot of things that I need to start from scratch and learn differently or opposite from what I’m doing,” he says. “I’m trying to utilize as many of the services that they have here. I’m in several different groups. The relapse prevention group. The depression group. I’m in the men’s group. I do the substance abuse group. I’m just trying to consume as much as I can. Like I did the alcohol. I’m trying to trade one in for the other. And it’s working. It’s a challenge. It takes some doing. It takes some effort.”

In March, Charles retired after more than two decades as a cook for the University of Cincinnati and UC Hospital. Recently separated from his wife, he spends three days a week at IKRON.

“I’m new at this, and already [retirement] doesn’t agree with me because I’m a person that likes to stay busy,” he says. “IKRON has the most structure for me right now rather than just laying at home … If I can get my [housing] placement and stuff together, oh I definitely intend to go back to work. I need the structure.”

To the question of what else he might want to share with readers, Charles thought for a minute. When he spoke, there were pauses between each sentence, as if he, too, was unsure what words would come next.

“I used to stay right around the corner from here for years back in the ‘70s. And I never thought to inquire what this building was about. Until, you know, I needed the services and found out through my brother that this is what they do,” he says.

“Some might have been just from my own guilt, shame, embarrassment to not explore those things,” he continues. “When I got so overwhelmed, it was like, they’re right there. They’re available … I just decided, you know, now’s the time for me to try and do something. I couldn’t do it by myself. It was either this or just kill myself, pretty much. I was going to just kill myself with my activities … It helped save my life.”