How the pandemic affected mental health and addiction services

COVID-19 changed the way we care for our region’s most vulnerable populations. The Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health organization pivoted quickly to care for people who needed it most during isolation.

A false premise

This article was initially envisioned as a necessity-as-the-mother of invention piece. Specifically, it was intended to highlight adaptations that mental health and addiction services providers employed during Covid and that they would continue to use once the pandemic’s threat receded.

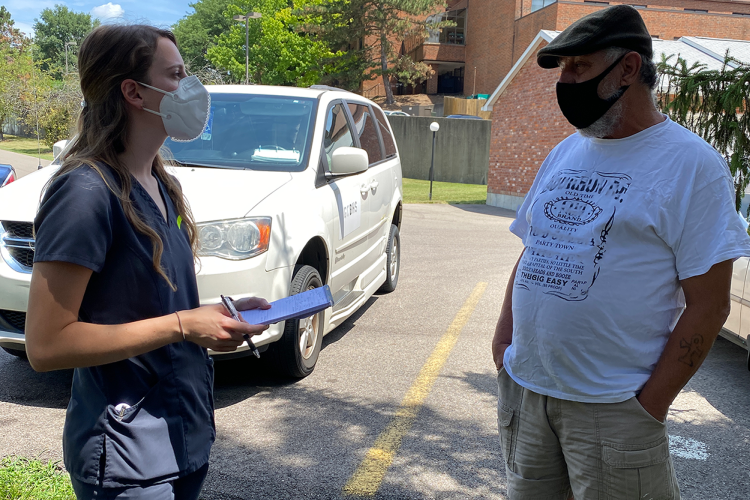

The vehicle for the article — literal and metaphoric — was Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health’s (GCB) injection van. Since COVID-19 made it risky for clients to enter GCB’s building on Madison and Victory Parkway, the van would bring nurses to the clients. The appeal of the injection van is clear: Even in a post-pandemic future, GCB clients, many of whom lack reliable transportation, would be met where they lived. In theory, this would increase efficiencies: fewer missed appointments, more clients served.

And indeed GCB needs to care about efficiency: It’s a sprawling health provider that serves 30,000 annually across Greater Cincinnati and has 630 employees.

But the real story of GCB’s work resists efficiency measures or neat computation. Rather, to grasp GCB’s work, we must look to its painstaking, deliberate delivery of and coordination of care for some of our region’s most vulnerable populations. This is unglamorous work, one that requires from its staff deep reservoirs of patience, compassion, and logistical moxie.

“Everything Comes Back to Rapport”

One Wednesday in late April, Linda Venturato finished her team meeting and prepared to visit Robert, one of her 83 clients. (To protect his privacy, Robert is an alias.) First, Linda stopped by GCB’s in-house pharmacy to pick up medications. Once on the road, she called Robert’s sister, with whom he was temporarily living in Bond Hill, to reconfirm her visit.

Robert is 62, and suffers from psychosis and delusions. Linda has worked with him since she started at GCB four years ago. To work at GCB is to become fluent in acronyms, and Linda serves as an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) nurse on the Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) team, the dual disorders being a mental illness and substance abuse disorder.

Linda is a psychiatric nurse much in the way that a Swiss Army knife is a multifunctional tool. Sure, she helps Robert organize his Zyprexa in his Mediset and administers the Invega Sustenna injection he needs to cope with his psychosis. However, in Robert’s case, owing to their rapport, Linda gives these injections not at the beginning but near the end of their 45 minutes together. Before then, she serves as a social worker, a trusted confidante, a mediator of familial grievances, and a scheduler of Robert’s expansive and continuous appointments.

And Robert’s care entails much scheduling because, in addition to his mental illness and substance abuse, his underlying health is poor. He has had all his teeth pulled and requires dentures, gets around with a colostomy bag, and desperately needs prostate surgery. Linda makes appointments and follows up for each of these ailments, coordinating the schedule so that either she or an IDDT colleague can transport Robert and be with him to serve as his medical translator and sounding board.

What Linda does not do is judge Robert or tell him how to live his life. When in the course of their conversation he tells her that he recently used crack, she says, “Are you still being kind of careful who you’re getting it from and how much you’re using?” When she asks if he’s still cooking and he says it’s harder to eat on account of his pulled teeth, she suggests mashed potatoes and ice cream—“but not too much of it.”

And when, after confirming a urology appointment where the doctor wants to see Robert immediately — his kidneys are failing — Linda calmly listens to Robert’s resistance to having surgery. Only then does she explain the risks of avoiding surgery, as well as gently point out that Robert’s continued cigarette and drug use can cause medical complications that mean he won’t be able to have the surgery at all.

“The people that we work with,” Linda says, have “a huge stigma against them. Because of their symptoms that often have not been managed and the problems that have come from that — like incarceration, housing issues, lack of food stability — they are misunderstood by the community. And they are alienated by the community. And so that’s where we come in to fill those gaps. Because every single one of my patients has trauma.”

For Linda, the purpose of her work resides in helping to build up her clients so they can be more independent. And in empowering them with the tools to do so.

Tracey Skale joined GCB in 1993, her first position out of medical school. Twenty-eight years later, she’s still at GCB, now serving as chief medical officer. Skale is a fast talker, personable, and an impassioned champion of GCB. In her own words, here’s how the organization navigated the challenge of the pandemic and how Skale sees its mission.

I remember it vividly because it was my birthday. It was March 21, 2020. It was a cold, dismal Saturday. And the leadership team met from eight in the morning till five in the afternoon trying to figure out how in the world we’re going to convert thousands of patients to telehealth. And then when we were exploring more, [we saw] we had 700 something clients that didn’t have a phone.

Almost all of our work [during Covid] has been phone calls, not seeing people. Lots of challenges involved in that. The shelters had pretty much disbanded because they couldn’t keep everybody close together with Covid so they’d have them in motels. And there were times with my homeless team I would get lists that would say, ‘Dr. Skale, for clinic today, call the Gateway Motel and ask the front desk for Room 108. Or I would call someone and they would be at the bus stop. Or in Kroger. And you’re just trying to catch people the best that we could. We got pretty good at it but we missed a lot.

Some of the things we missed is that, first of all, the isolation factor for our clients has been huge and a very sad thing. Sometimes our clients’ only contact has been with our care managers. Unfortunately, a lot of our clients don’t have a lot of natural supports. They don’t have family and so we become that for them.

We saw definite increases in depression and anxiety. We definitely saw increases in suicidality. We’ve definitely seen more relapses with sobriety.

I had one of my gentleman tell me he had fifteen years of sobriety. And he said he relied on AA meetings — live in-person meetings — and when he didn’t have that, and he didn’t have Zoom capability, he said, ‘I feel like I’m going to drink again. I didn’t drink in fifteen years, but I think I’m going to drink.’ People need human contact.

The kinds of people that we’re helping feel better are some people that society would think, ‘Oh, wait, that person must be in a hospital somewhere in a back ward.’ But what they don’t realize is that world doesn’t exist anymore, and for good reasons. The days of being in a hospital just because you’re feeling a little depressed are gone. So when you’re in the hospital now, you’re in the hospital because you’re at imminent risk of harming someone else or yourself, or you’re so psychotic that you can’t put a spoon to your mouth to feed yourself. And you stay in the hospital a very short period of time. So we’re taking care of people that most people would think would be in a hospital somewhere but they’re not.

It’s really complicated. We like streamlined approach to meds, but there are people on complicated psychopharmacological meds, but also diabetes meds, hepatitis meds, and this and that, and by the way, they’re using crack. There’re so many things we’re thinking about.

We do this work with open arms. It’s so incredibly fulfilling, rewarding. This doesn’t mean there’s not challenges. Every day I leave here, I think I’ve learned so much from my clients, about resilience mainly.

Picture living with zero money. I’m not even talking about a hundred dollars, a thousand dollars. Zero money. How in the world do you get by? People that will say they never had a key to a place that was their own and they’re sixty something. Or they had to ask people for soap and toilet paper. Can you imagine? That’s part of empathy. You put yourself in people’s shoes. I am floored by the strength of people.

Consultants will come in every several years and say, ‘Oh, you could be more efficient. You could do 10-minute appointments. And I always say, ‘Not while I’m medical director.’ Because that’s not what we do. We don’t just write a prescription. We’re engaging, we’re talking. We’re getting to know you.

With thousands of people, we still take one person at a time. Yeah, I might have 500 people on my caseload, but if you’re my patient and you’re sitting there right now, you are now the center of my universe and you have my undivided attention. And we’re going to figure this out for you.

“I was used to living on concrete”

Derick Shores lived on the streets for thirteen years. A West Virginian, he followed a girlfriend to Cincinnati. The relationship ended but Derick’s drinking increased, and he became an alcoholic.

This past fall Derick moved into the Tender Mercies Flats on Ezzard Charles, where he is one of roughly forty GCB clients. His apartment has its own bathroom and kitchen, and it’s clear Derick is immensely charmed by it.

“I was so used to being homeless,” he said, “I didn’t even realize I wanted my own place. Now I got this place, I kind of run home every chance I get,” he says. “‘Hey, I can cook my own food, I ain’t got to be out here.’”

Helping clients secure housing is a key component for GCB, one that anchors its wrap-around services model. Derick’s associate case manager, Lashann Saunders, works out of an office in the building, and she sees Derek and her other 34 clients who live here every day.

So long as he adheres to the rules, Derick can live in his apartment indefinitely. And GCB’s holistic service delivery model is working for Derick, who says as a client, you “learn stuff without realizing you’re learning it.”

Derick’s newly successful housing situation, however, conceals vast bureaucratic mechanisms, one that Jamia Smith, a GCB housing support specialist, must continuously navigate. Even before the pandemic, Cincinnati had a housing shortage, and COVID has further shrunk available beds as shelters had to restrict their numbers and house people in motel rooms.

“When you start talking about housing, you’re opening a pandora’s box,” GCB’s community relations manager Dawn Michaels says.

In terms of housing, Derick is among the fortunate ones. He came onto Jamia’s radar through another unit within GCB, Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness (PATH). Two members of the PATH team spoke with Derick in Fountain Square and got him to agree to be connected to GCB. From there, the year-long process to qualify for a Certificate of Homelessness began, a document necessary to prove Derick’s chronic homelessness and that he will need to secure long-term housing.

The logic behind the certificate makes sense. States and municipalities confront limited resources. And so the intricate checklists and forms that Jamia Smith must work with Derick to complete are critical to providing him with the care and support he needs.

The hours Jamia and her colleagues spend on the phone and email with state agencies, housing authorities, and nonprofits are not the stuff of a Hollywood movie. Just like much of GCB’s work, it is not flashy but it is essential.

Each week Jamia receives fifteen new clients whose housing needs she must assess and hope to place. Each is another person GCB is trying to prevent from slipping through the cracks so that they can live better lives.

Alexander Ralph is a lecturer at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, where he teaches expository writing and courses on storytelling through public policy. He is at work on a novel set in 1970s Detroit and is also the editor of the Corruption in Fragile States Blog. An article he wrote on Hamilton County’s Mental Health Felony Court appeared last summer in the Cincinnati Enquirer.