Tired of waiting, Ohioans are framing their own solutions

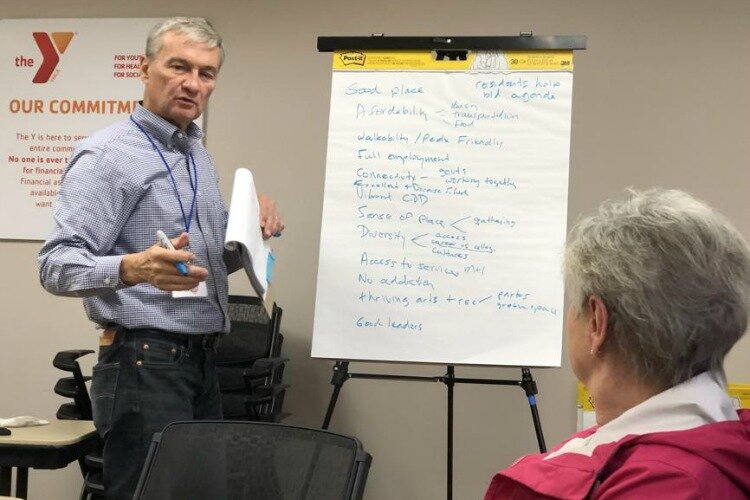

The 37th Your Voice Ohio community conversation focused on the angst and complexity of statewide issues, but also on problem-solving through collaboration.

It was a Monday evening in a spiffy YMCA community room in suburban Springboro, Ohio, once a sleepy Shaker village, now a congested, upscale expressway exit between Dayton and Cincinnati.

The 37th Your Voice Ohio community conversation, co-sponsored by local media in an experiment to better connect journalists with the communities they cover, was about to begin.

Tables were optimistically set for 12 people.

Only five showed up.

As one Springboro participant said: “People get up in the morning, turn on the lights, flush the toilet, the school bus comes on time — there’s no problem here.”

But that’s okay. Add that five to the 1,200 Ohioans who have attended Your Voice Ohio meetings in the last two years and the voices deliver powerful messages that journalists can use to hold leaders accountable.

And this isn’t just for journalists. People feel empowered. One woman walked out of the Springboro meeting determined to run for office. A Kettering teen wants to launch a voting awareness effort at school. Officials in the Parkersburg-Marietta area launched a study on how best to treat addiction. A white Akron suburb launched a full-force effort to embrace diversity.

Two worlds emerged in the Your Voice Ohio conversations — the once-thriving industrial communities vs. the higher-income, college-educated areas. They had significantly different life experiences and immediate needs, but also had shared concerns.

Where they agreed: A need for respect for those different life experiences; jobs with dignity; health care; education that gives everyone a fair chance; mental health resources; transportation; a strong sense of belonging; and, most of all, hope.

That desire for hope led them to admonish news media: Stop telling us Ohio is in decline, we already know it — we’re the numbers that show it. Help us fix it.

And they are tired of waiting for government. Communities that suffered the most and the longest — Dayton and Warren — appeared to be entering a new phase. Feeling abandoned, there is talk of redefining happiness and strength from within.

The complexity of Ohio

Higher-income, more educated communities are islands in Ohio. The state as a whole ranks among the worst for economic and quality-of-life decline in the last 20 years. On these islands people are less likely to show up for conversations designed to fix problems because lives are busy and towns are perceived as good. Nonetheless, participants expressed concern:

Mental health: Pressure on young people in particular to attend college, and the likely debt load that would follow, creates unhealthy family anxiety. One college instructor blamed mothers, herself included, for creating family and community tension by disparaging those who do not go to a four-year college, and not just any college.

Addiction: The realization that addiction is pervasive in upscale communities was deeply troubling. In those communities, people said the problem must be openly discussed if it is to be addressed, and for some it caused a reevaluation of decades-old perceptions that drugs were an urban or race issue.

Diversity: There was a perceived inability in white communities to respect their own differences — particularly over politics, religion, addiction, and college vs. skills — and also cultures and race. In two pre-election community meetings in suburban Green between Akron and Canton, people said diversity was critical to helping children navigate the world and to attracting forward-thinking employers.

Aging population: Seniors who raised families in rapidly growing suburbs are frightened by retirement prospects. The communities they call home generally do not have affordable senior living, walkable town centers with doctors, stores, or convenient public transportation.

The angst

Remember: Those upscale communities are islands. They may represent 20–30 percent of Ohio — something close to the college-educated population.

In the other 70–80 percent, needs are more basic. Journalists heard:

- We need healthy food.

- We need affordable housing.

- We need safe neighborhoods.

- We need transportation.

- We need help educating our children.

Are candidates echoing these concerns? Are journalists addressing them?

In Dayton, a participant asked why private utilities are required to faithfully provide electricity, but food companies can withdraw a most basic need from entire communities. Left behind are convenience stores with high-salt packaged foods that cause public health problems.

In Trotwood, a predominantly black suburb of Dayton, one person said they’re forgotten. Torn siding and splintered roofs from a tornado last spring are still apparent. Schools score poorly.

The state was ordered by the courts to fix school funding 20 years ago, the state did not, and now Trotwood children suffer, a city official said. How can they improve school performance, she asked? There is no tax base to raise property taxes. Can the city government help with income tax revenue? There’s too little income to tax.

Maybe people could get involved, a former Trotwood councilman said. But how would you spread the word? There is no local news source.

Nonetheless, this small group echoed a solution heard in conversations in Dayton: If the state won’t save us, we’ve got to work regionally to save the children.

The Your Voice Ohio community meetings climax with that: Problem-solving.

Even in the most troubled communities, people become energized about where they can agree and what they can do.

There’s a message there for the leadership elite, for the journalists, for the so-called experts: People in Ohio are framing their problems and solutions in their own ways, they are creative and collaborative, and they are tired of waiting.

To read more about the project and view the report, visit YourVoiceOhio.org.