Krista Taylor and Gamble Montessori: “I really believe that we change lives”

When Krista Taylor received Cincinnati Public Schools' "Educator of the Year" award, she donated the $10,000 prize to her school, Gamble Montessori, to help students attend a marine biology bootcamp.

A public Montessori high school is rare enough in the United States. Rarer still is a public Montessori high school that defies the privileged stereotype to serve an economically-challenged population.

As a Title 1 school, with roughly 70 percent of students qualifying for free lunch, James N. Gamble Montessori High School in Westwood falls into that rarer-still category.

“That’s an anomaly that doesn’t exist maybe anywhere else,” says Krista Taylor, junior high intervention specialist at Gamble.

In the Cincinnati Public School District (CPS), the younger, smaller Gamble sits in the shadow of the well-regarded first-Montessori-high-school-in-the-nation, Clark Montessori in Hyde Park. But it’s worth taking a closer look at Gamble — an honors-level, college preparatory school — in part because of teachers like Taylor.

Taylor earned citywide attention last spring when she received the Dr. Lawrence C. Hawkins Educator of the Year Award for 2014-15, receiving a $10,000 prize from Western & Southern Financial Group for being CPS’ top teacher. She promptly gave the money to her school.

Taylor’s donation will make it possible, over the next three years, for 12 eighth-grade students to attend a marine biology bootcamp in Pigeon Key, Fla. The eight-day trip also serves as a rite of passage and an opportunity for the students to bond with each other before entering high school. Teachers and parents write letters to the students, and on the last night students are given a packet and sent off to find a place to read the letters.

Last year, only half of the school’s roughly 100 eighth-graders were able to raise the $1,800 required to participate.

“It’s such a tenuous time for a child, so as a developmental component to their growth that may be the most powerful field experience we offer in the building,” Taylor says.

Her donation will provide $1,000 toward the trip to four students — one from each of Gamble’s junior high “communities” — each year for the next three years. The scholarship will be awarded based on perceived financial need and a student’s character strengths, not grades. The students will have opportunities to raise the rest of the money themselves.

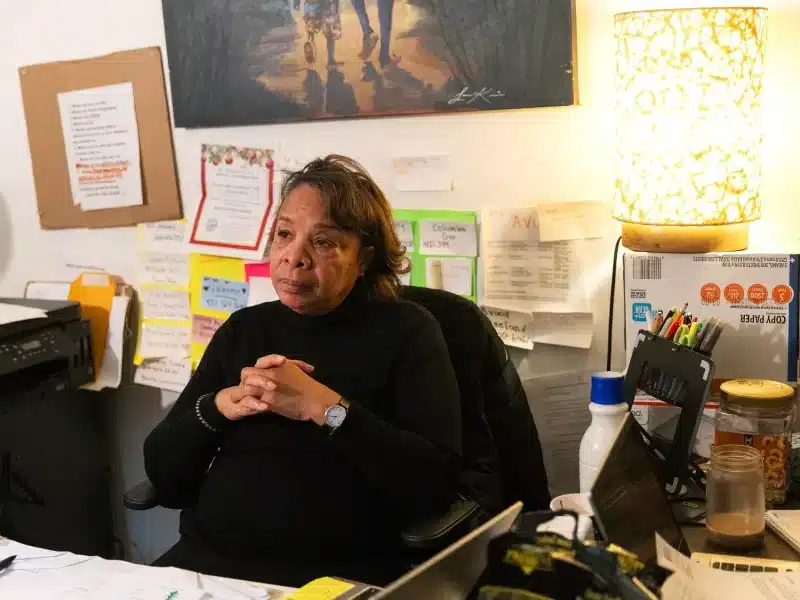

“We’ve had a lot of success at this school, and no small portion of it is because of Krista’s diligence and dedication,” says Jack M. Jose, in his seventh year as school principal. “That’s who she is. Her first thought is ‘How do we help this community? How do we give to the students?’”

Taylor insists on deflecting the attention.

“I’m just one person, and Gamble is a very wide, wide web,” she says.

One thing Taylor and her colleagues agree on: They’re proud of the school and its work to create a culture of cooperation and collaboration and of educating the whole student.

Last year, Gamble was the only CPS school with an A grade in the “value-added” category, which measures academic growth in the school’s students. It’s just one grade, and it’s hard to assign too much meaning to any school measurement right now, given the constantly changing Ohio report card.

While Jose is pleased with that value-added A, he believes his school’s mission goes beyond preparing students academically. Learning and teaching grit and perseverance is a common theme in talking to the team at Gamble.

“In today’s society, a school is more than a place where we just pass on information,” Jose says.

Visit Gamble Montessori, and here’s what you’ll find:

• Everyone is welcomed every day.

“The worst crime that I think could happen is that a child daily walks into a classroom where the teacher isn’t warm, where the teacher isn’t welcoming,” Jose says. “How hard must that be? There are dozens of heroes sitting in your classroom every day for what they did to get to your front door. If you don’t hug them, if you don’t welcome them, if you don’t greet them, shame on you.”

• Community and collaboration, for both students and teachers.

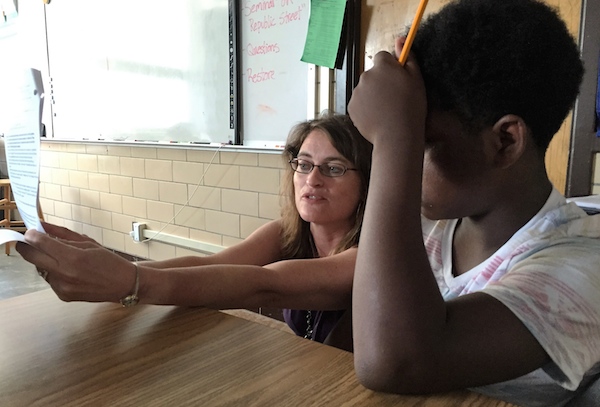

Seventh- and eighth-grade students are divided into four “communities” of 50 to 60 each and assigned a team of teachers. Students chose the names and created and selected logos within their communities. Taylor heads up United Leaders, with two teaching partners.

Beau Wheatley teaches Social Studies and Language Arts to United Leaders with Taylor. He arrived at Gamble a little more than three years ago as a first-year teacher. Wheatley says he and other new teachers have benefitted from the school’s formal one-on-one mentoring from experienced teachers.

And he’s learned from watching Taylor, too — as he describes a true team teaching model, planning classes together and sharing the work, dividing the lead on lessons.

“A lot of the students don’t know Krista is an intervention specialist,” Wheatley says. “She takes on the role of planning and teaching every student. She is on the front line of changing the way teaching should be crafted. Every lesson is designed to meet the needs of all students in the classroom.”

• Field experiences are core to the Gamble (and Montessori) model.

Experiences outside the classroom are built into the academic program. Community service is required, even of junior high students.

Seventh-graders attend Leadership Camp the fall after they arrive at school, and high school students have two two-week intercessions each year that take them into the Greater Cincinnati community and beyond.

• A focus on the positive.

It’s embedded into the Pigeon Key scholarship process. Taylor has asked that teachers sit down with students selected to receive the funds and intentionally describe to the child his or her character strengths, those special and individual qualities.

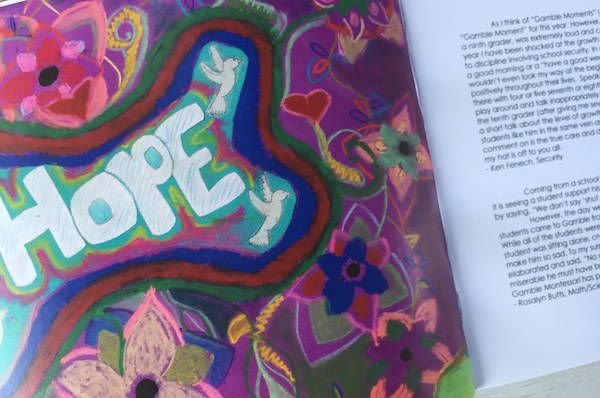

Taylor imagined, then spearheaded for the last two years, a little book of faculty and staff stories from the year called “Gamble Moments.” Her idea was that capturing these inspiring moments would help every adult in the building understand the impact they were having.

“What we do is very challenging,” Jose says. “It’s so easy, it’s the human condition really, to go home and talk about what went wrong with our day. But we need to change our own hearts and our own minds, intentionally, to focus on what was good about this day, to remind ourselves why we love this job, why we love our kids. The ‘Gamble Moments’ book is a powerful way to do that.”

Discipline at Gamble focuses on teaching new behavior instead of punishment.

“Even when they’ve done something wrong, they know that even in the midst of getting that consequence they’re going to be treated well, they know they will be greeted, that they’re welcome at the school, that a poor choice doesn’t mean you’re not part of the community,” Jose says. “It means you made a poor choice. You’re going to get a consequence, but we’re going to grow you in that way.

“If you misbehave, and my consequence to you is that I send you away several days, I’ve missed an opportunity to teach you the right way to behave in that situation. That’s the ethos of our school, understanding that we’re always teaching student behavior.”

That being the case, students are learning a powerful lesson from Taylor’s selfless gift — one that’s potentially life-changing for at least a dozen students.

“I want people to know who we are and what we do, to understand its value,” Taylor says. “I really believe that we change lives … and sometimes we save lives. At the bare minimum, we plant seeds that allow students to access something different should they wish to do so in the future.”

That doesn’t just apply to teachers at Gamble, she says.

“We’re all giving all of ourselves every day to classrooms of students with unmeasurable needs, regardless of what kind of program you’re in, suburban, private, public, charter,” Taylor says. “Every child comes to school every day with a plethora of unmet needs. And we’re trying to meet them all. And we’re doing the best we can. And it takes a tremendous amount of endurance and dedication and caring and patience, and we don’t always do it right, and that’s OK, too.”