Art of, by and for the people: CAM presents American folk art

Now through Sept. 3, the Cincinnati Art Museum presents A Shared Legacy: Folk Art in America, the most expansive array of American folk art ever displayed locally.

Some artists are trained in art schools; others develop creativity on their own. Works by the latter are sometimes called “primitive” because they don’t follow the standards of cultivated art. But they can still be eminently expressive and thought provoking. They are often decorative in plain but artful ways that evoke simpler times. And sometimes they function as harbingers of future art that’s admired today.

The temporary exhibition currently at the Cincinnati Art Museum, A Shared Legacy: Folk Art in America, celebrates art rooted in personal and cultural identity and made by self-taught or minimally trained artists. Created by everyday people instead of individuals with refined tastes and training, folk art was common in the United States between 1800 and 1925. CAM’s exhibition offers more than 100 pieces, with roughly 60 from esteemed folk art collector Barbara L. Gordon. With 40 additional regional loans, this is the most expansive array of American folk art ever displayed locally.

At the exhibition’s opening in June, Gordon told me she was introduced to folk art in Colonial Williamsburg on a seventh-grade trip from Cleveland. As an adult, her passion for folk art and historic toys continued. “I saw those objects — whirligigs, decorated, painted furniture, blanket chests and cigar-store figures — and I just knew that’s what I wanted to collect.”

Asked what appeals to her about folk art, Gordon said, “A lot of it is the shapes and the colors — and the whole idea that you can learn a lot about early American life. These objects tell you so much about history, and they’re beautiful.”

At first, Gordon spent five years acquiring a broad array of folk art. But then, she says, on the advice of a respected dealer, “I sold everything and started again, trying to stay disciplined and just buying great objects to build a great collection.”

A Shared Legacy takes up CAM’s two large temporary exhibition spaces on the second floor. It encompasses a broad range of items — still lifes, landscape paintings and portraits, pottery, furniture, quilts, embroidery and textiles. Additionally there are numerous fanciful items such as a small, carved carousel, weathervanes and various spinning toys called whirligigs.

Painter Edward Hicks (1780-1849) was repeatedly inspired by a passage from the Bible’s Book of Isaiah: “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” Between 1818 and 1849, he created as many as 100 versions of The Peaceable Kingdom. A rare example in the CAM show is his The Peaceable Kingdom with the Leopard of Serenity. As in many of the paintings in A Shared Legacy, Hicks used images that are flat, simple and brightly colored — but still highly evocative.

Portraits are similarly crafted using this simplified, straightforward style. In an era before photography, paintings of family members were often the only way to possess an image of a loved one.

Works often did not employ perspective as practiced in more refined art forms. Henry Dousa’s 1875 painting of The Farm of Henry Windle features an immense bull, vastly larger than the nearby farmhouse. Rather than a naturalistic representation, this indicates the artist’s — and likely the farmer’s — sense of what was most important and worthy of pride. Gordon observed, “Folk artists didn’t always get everything accurate, but their works are charming.”

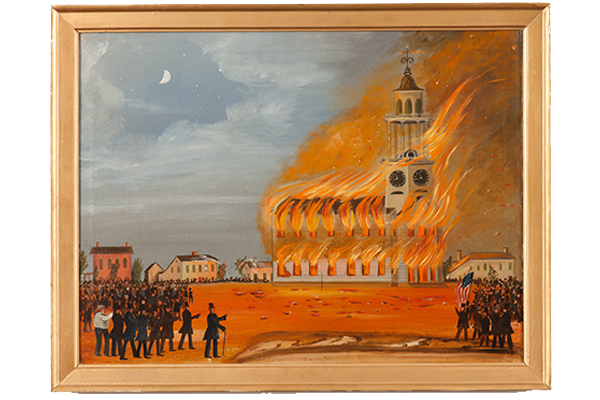

A trio of images by John Hilling depict the 1854 burning and looting of Old South Church in Bath, Maine, during a wave of anti-Irish Catholic sentiment. These images represent another function of folk art before photography was broadly available, documenting a sequential event as a newsreel might a century later. (A clock in the church’s tower advances in each painting.)

This exhibition will appeal to families. The more fanciful items will amuse kids, while adults can appreciate the skill required to decorate furniture, sculpt birds and paint landscapes. Gordon calls folk art “the art of the people, by the people and for the people, representing what it was like at the beginning of our country.” She added, “I think visitors will love the objects because they are so beautiful. They and their children will learn what it was like: Not many people could read in the 19th century, so cigar-store figures and simple signs said, ‘Come in! We sell tobacco!’ or ‘It’s a haberdashery! We sell clothing.’” These appeals to everyday folks still have the power to attract.

A Shared Legacy is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum, one of the oldest art museums in the United States, through Sept. 3.