Calling All Volunteers: Why more young people spend a year working for free

For many Cincinnatians who commit up to a year of their lives to full-time unsalaried service, volunteering is a way of life. Meet four who make a real difference.

About one in four Cincinnati residents volunteer, according to the Corporation for National and Community Service. Some work at a school bake sale, others collect trash at a community clean-up.

For more than 200 people in Greater Cincinnati, however, volunteering is a way of life. They’ve committed nine months to a year of their lives to full-time unsalaried service. Here are a few of their stories.

Antonio Allen, Public Allies

“People make a lot of assumptions about kids in foster care,” Antonio Allen says. “They think they’re unwanted by their families, troubled or a danger to society.”

Allen experienced these biases firsthand from age 15 to 18, when he lived with two different foster families before moving into an independent living program.

Now he helps others in foster care through a year of voluntary service through Public Allies with the CHECK Foster Care Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“I think I can provide added perspectives that are beneficial to both the kids and others involved,” he says.

Among Allen’s projects in this role is a study with individuals ages 18-21 who are transitioning out of the foster care system to assess their skills and knowledge about accessing healthcare.

“Hopefully, after meeting with us (over the course of a year) and receiving the information we provide, their visits to the hospital will be less frequent, and they can handle medical issues more efficiently and with better understanding,” Allen says.

The study requires participant to provide candid information about their healthcare practices and knowledge, and Allen’s shared history allows him to build trust.

“Our participants are more willing to open up once they hear that I was in foster care too,” he says.

Allen loves that Public Allies provides him the opportunity to give back in this way, but he also appreciates the program’s practical benefits, including experience in his field (he has a BA in health science), deferred student loans and a $5,700 educational stipend he can use to pay back those loans once he completes his term.

Allies also receive weekly leadership training and work with each other and community partners to develop a project that will continue long after their year of service is complete.

“Getting the project done with little time is the most challenging part of this experience,” Allen says.

He knows a little bit about having limited time.

“Sundays and Monday nights are the only times I’m not working,” he says.

Since his Public Allies role provides only a small stipend, Allen works a second job on evenings and weekends. When asked what he’d like to be doing 10 years from now, he says, “I’d like to go on a vacation.”

“Public Allies is pretty stressful even without a second job,” Allen says. “Having to work at the placement, do trainings and collaborate on a service project takes a toll on every person involved. But these people are still willing to sacrifice their time and energy for the chance to positively impact someone’s life. There are groups and groups of people like that … we’re not unique. I think the core of humanity is that everyone is just trying their best.”

Andrea Rosado, Vincentian Volunteers of Cincinnati

Before starting medical school at the University of Cincinnati last fall, Long Island native Andrea Rosado spent a year in the West End providing free pharmaceutical care at St. Vincent de Paul’s Charitable Pharmacy.

“I wanted to do a year of service because it would give me the opportunity to form connections with people,” she says. “I liked the Vincentian Volunteers of Cincinnati (VVC) specifically because it prioritizes living in solidarity with the poor and being part of an intentional community.”

Although her role at St. Vincent de Paul was primarily to enroll patients in the pharmacy program, it soon turned into much more. As the only bilingual pharmacy assistant, she was often called on to help with much more than a simple intake.

“There aren’t as many people to help the Spanish-speaking clients, so I did whatever I could,” Rosado recalls.

She tried to do everything from finding people beds to paying their rent but found there was a limit to how much assistance she could provide.

“Sometimes the most I could do was to give them compassion and give them myself,” she says.

On those especially challenging days, Rosado appreciated living with four other VVC members who understood what she was going through.

“Being part of an intentional community is more than just having roommates,” she says. “It’s more like a family. You work together toward common goals, pool resources and factor the community into your decisions. It requires really making an effort to be present to each other.”

VVC focuses on faith, friendship and services and encourages simple living, and workers were challenged to figure out what that meant to them. Because their monthly stipend is small ($100 per month), VVC members signed up for food stamps/SNAP and then tried to eat simply enough to have some SNAP money left over to purchase items for St. Vincent de Paul’s food pantry. They took the bus even though they had access to a car, and they turned the thermostat a few degrees lower than prefered.

“We basically just tried not to give in to convenience, and we grew because of it,” Rosado says.

She says the best part of her VVC year were the relationships she built with clients, staff and other community members and advises individuals not to count out a year of service just because it doesn’t seem to match with future goals.

“Whatever skills you have, there is a way to utilize them in service,” Rosado says. “Just be present and always have your eyes, ears and heart open.”

Megan Knapke, Notre Dame Mission Volunteers

Megan Knapke isn’t a typical full-time volunteer. She’s married and worked full time in a “real” job for five years.

“I wasn’t happy or fulfilled in my job, but I didn’t know what the next step for me would be,” she recalls.

So when she heard about a discernment retreat for current and past full-time volunteers — she had done a year of service right out of college — she jumped at the opportunity to attend.

“When I came home, my husband could see this spark,” Knapke says. “He knew this is what I needed to do and supported my decision.”

Knapke quit her job and joined the Notre Dame Mission Volunteers, a program geared toward individuals of all ages who are interested in using education as a tool to foster empowerment in economically disadvantaged communities.

She currently provides social and emotional life skills and tutoring to sixth through eighth graders at Oyler School in Lower Price Hill. Oyler received national attention in 2015 with the release of a documentary film highlighting the Cincinnati Public School’s efforts to reach beyond the classroom to help the traditionally poor, Urban Appalachian neighborhood succeed.

“I’ve fallen in love with this neighborhood and these kids,” Knapke says. “I feel like I’ve been accepted and gained their trust. We talk about the future, and they’re starting to consider possibilities they never had before.”

She stresses that she isn’t at Oyler to be some sort of savior but instead to be a mirror that allows the kids to see their own potential.

“It’s not about coming in and doing service,” Knapke says. “It’s more than that. It’s about building relationships and creating understanding.”

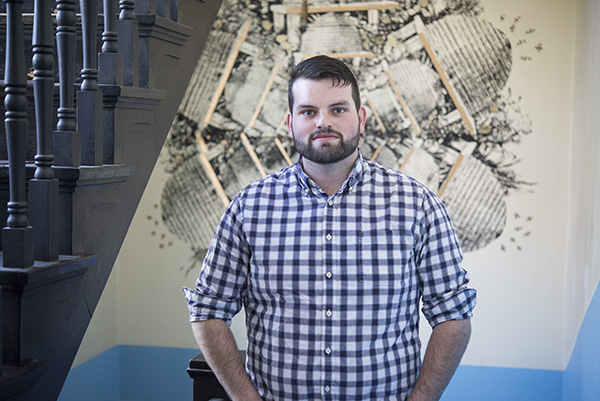

David Beck, Santa Maria AmeriCorps

“It’s heart-wrenching hearing people’s stories,” says David Beck, a member of the Santa Maria AmeriCorps program in Price Hill. “They come in crisis. Either they just lost a job or feel very lost in life. But it’s the most rewarding thing in the world when you see them pick themselves up again.”

Beck works as a job coach with Santa Maria Community Services, helping clients develop goals and gain the skills they need to accomplish those goals.

“It starts with just getting to know each other,” he explains. “I learn about them on a personal level and a financial level. We discuss how they got to this point and how they might right whatever they consider wrong in their lives. I have to sometimes ask uncomfortable questions, but as long as they know it comes from a place of love and understanding, they get it.”

Beck graduated with a degree in business administration, but he now thinks service may be his career.

“You’ll never get rich doing nonprofit work, but that’s not what it’s about,” he says. “It’s about the work. The clients know you on such a personal basis. They consider you a friend. They even leave you little thank you notes and stuff. It’s awesome.”

Beck says being part of Santa Maria AmeriCorps has reinforced his values and reminded him to withhold judgment.

“You never know where someone is coming from or what kind of day their having, if just saying ‘Hello’ might mean the world to them at that point,” he says. “In this job, you see people from all walks of life in all manners of crisis. It’s humbling and enlightening.”

He encourages others to consider a year of service.

“It’s important to get out of your comfort zone, especially the year right after college,” Beck says. “I’ve had to put my pride aside and go on food stamps. I do landscaping on the side to make ends meet. I’ve learned budgeting. I’m wearing St. Vincent de Paul clothes head to toe.”

He says he’s gained invaluable skills and contacts that will be beneficial throughout his life.

“Even if you can’t volunteer for a year, do it for a couple of months or even a day,” he says. “It’s important.”