Soapdish: Fanny Trollope and the domestic manners of Cincinnatians

In the afterglow of the Cincinnati sister march, Soapdish columnist Casey Coston muses on ladies of note throughout history and one in particular: Mrs. Frances Trollope, whose impressions of Porkopolis were less than celebratory.

On a recent balmy, 60-degree Saturday in January, I found myself at the largest political rally I have ever seen in Cincinnati. The local edition of the national Women’s March drew significant numbers for the pre-march rally and an even larger crowd — estimated at up to 14,000 people — for the actual march.

It’s hard to say exactly how many were in attendance, however, since no media outlet deemed it significant enough to send out a drone, let alone a helicopter for aerial footage — apparently reserved for all-too-important homicides or I-75 fender benders.

Nevertheless, as we marched out of Washington Park and down Central Parkway, I found myself reflecting upon a few of Cincinnati’s esteemed female luminaries over the years — Civil Rights activist and former vice-mayor Marian Spencer; sharpshooting cowgirl and musical-inspiring firebrand Annie Oakley; talk show host and media vanguard Ruth Lyons; abolitionist and Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe; and Elizabeth Nourse, Cincinnati’s most famous female artist, widely unrecognized though depicted in the ArtWorks’ mural on Eighth Street.

But the story I absolutely love, and one that gets far too little attention in the annals of Cincinnati history, is the short, impressive presence of one Frances “Fanny” Trollope. Trollope, few will recall, made her imprint on the literary world with The Domestic Manners of Americans, a fairly wholesale and scathing indictment of the 1830-era American republic, and an absolute skewering of Cincinnati in particular.

Time and again I have regaled associates with “Trollope’s Tales,” and am consistently fascinated and appalled that nobody is familiar with her story. Now, with Feb. 10 and the 189th anniversary of “Old Madam Vinegar’s” arrival upon us, it is high time we revisit this tale which, if fictional, would undoubtedly inspire a BBC miniseries… and perhaps still should.

Trollope came to Cincinnati in 1828 via a somewhat circuitous path. Back in England, her husband had been an unsuccessful barrister with few, if any, clients. Her anticipated inheritance went awry when her elderly and widowed uncle remarried and was blessed, miraculously, with a May-December heir. The Trollopes, meanwhile, had erected a grand mansion on leased land while counting down the days to the ill-fated birthright.

Looking for a life raft in the seemingly elysian fields of opportunity in America, Trollope was inspired by the writings of reformer Frances Wright, whose 1821 book Views of Society and Manners in America was chock-full of effusive praise for this new land of boundless resources and egalitarian beliefs. Wright had spoken highly of a utopian colony she founded in Nashoba County, Tenn., based on the teachings of Robert Owen.

Thusly inspired, Trollope left her floundering husband in England to tend to his non-existent law practice and set sail for Utopia, located, in this case, just outside Memphis. Trollope brought with her a select three of her six children, as well as a young French artist by the name of Auguste Hervieu, ostensibly to teach drawing at Nashoba.

She had barely set foot on our savage shores when the grumblings started. As her party made its way north on the Mississippi, Trollope directed her ire of the moment at the mode of transport.

“Let no one who wishes to receive agreeable impressions of American manners, commence their travels in a Mississippi steamboat; for myself, it is with sincerity I declare, that I would infinitely prefer sharing the apartment of a party of well-conditioned pigs,” she wrote.

The porcine reference proved to be prophetic, as we will see later on, and things proceeded to go downhill from there.

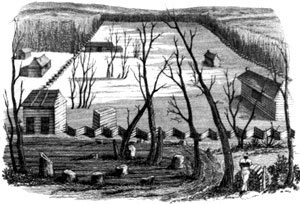

Finding Nashoba to be less than utopian, and more a dismal mud pit of log cabins and stumps, Trollope turned her sights to Cincinnati, then a promising city of 20,000 and growing. She packed up her children and, curiously enough, her traveling French artist, and boarded a steamboat for Cincinnati, intent on wowing the citizenry with her genteel British charm and sharp intellect.

As noted in the WPA Guide of 1943, “Mrs. Frances Trollope, late of England, huffed across Public Landing, flanked by her children, to see what she could do about improving the family fortunes…Mrs. Trollope went about Cincinnati like a child at the zoo for the first time. She thought people rough and uncouth, and giving to strange practices.”

In particular, she singled out for derision the “eternal” handshaking, as well as the men, who were seemingly permanently enveloped in a malodorous cloud of whiskey and tobacco.

Trollope’s entourage settled about a mile and a half from what was then the downtown area, in the Northern Liberties, at the southeast corner of Dunlap and McMicken, in what she was arguably the first to deem the “Village of Mohawk” (now Mohawk Hill).

Casting about for a cause, she jumped in feet-first with the newly founded Western Museum, the first museum of natural history west of the Alleghenies, and what is now known as the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science at Union Terminal. Cincinnati was at the time still trying to get its hands around the concept of the nonprofit museum, which included collections of fossils, botanical specimens and minerals. By all accounts, the collection, while scholarly, was wholly uninteresting to the general public. The museum continued to struggle, while also adding wax figures of historic characters such as George Washington that were sculpted by a then relatively unknown Hiram Powers.

Seeing an opportunity, Trollope immediately enlisted her French companion to collaborate with Powers on a lurid and sensational exhibit based on Dante’s Divine Comedy, with a pointed emphasis on the most graphic details of Hell. The public was outraged; the museum was a success and, along with director/owner Joseph Dorfeuille, Trollope hatched an idea for even more vaudevillian entertainment — the Invisible Girl, the Magic Chamber, Mysteries of Egypt! — a veritable Ripley’s Believe it or Not, and Cincinnatians lapped it up.

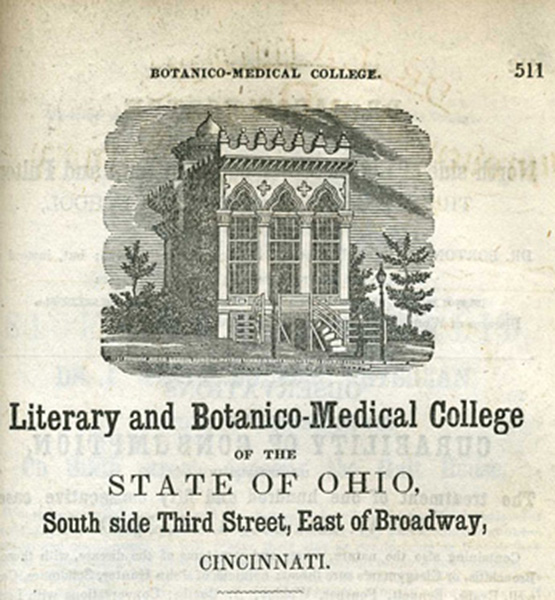

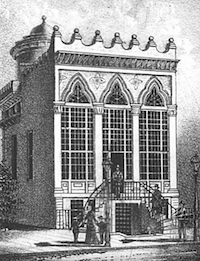

Flush with the success of these sensational museum exhibitions, Trollope was ready to take her game to the next level, a plan that partly involved improving Cincinnati’s skyline, while also improving her family coffers. She decided that Cincinnati wanted “domes, towers and steeples,” and to address the deficiency, she combined all three of those features in her aptly-titled Trollope’s Bazaar, at 411 E. Third St., just east of Broadway near where the I-71 tunnel is located today.

The gaudy Moorish-Byzantine-Greek-Egyptian-whatnot inspired architecture of Trollope’s Bazaar featured a main hall lined with two rows of columns. Domes, cupolas and spires graced the rooftop. Inside were several salons, a bar, an exhibition hall and a ballroom. Trollope stocked it like an exotic department store, featuring cheap goods from abroad that her husband would procure at low prices, as well as locally purchased merchandise, which she would then heavily mark up for the unsuspecting populace.

The Cincinnati public was thoroughly unimpressed — and not so unsuspecting, as it were. Amid dismal failure, Trollope was forced to file bankruptcy, no doubt further cementing her dim view of Cincinnati. Trollope’s Bazaar went on to later stints as the Ohio Mechanics Institute, then a bordello, and was eventually torn down around the end of the century.

Trollope, meanwhile, was financially destitute. Although she had once mentioned preferring the company of pigs, living in Cincinnati had given her a whole new appreciation of the then-thriving Porkopolis.

Observed Trollope: “If I determined upon a walk up Main Street, the chances were five hundred to one against my reaching the shady side without brushing by a snout fresh dipping from the kennel; when we had screwed our courage to the enterprise of mounting a certain noble-looking sugar-loaf hill, that promised pure air and a fine view, we found the brook we had to cross, at its foot, red with the stream from a pig slaughterhouse while our noses, instead of meeting the ‘thyme that loves the green hill’s breast,’ were greeted by odours that I will not describe, and which I heartily hope my readers cannot imagine.”

Ironically enough, Trollope’s extreme disdain for Cincinnati would prove, in the end, to be her financial rescue. She left Cincinnati in March 1830 and returned to England. In 1832, she published her now-famous screed The Domestic Manners of Americans, in which she detailed the horrors impressed upon her during the sojourn, reserving the majority of bile for Cincinnati and its residents: “We quitted Cincinnati…and I believe there was not one of our party who did not experience a sensation of pleasure in leaving it. We had seen again and again all the queer varieties of its little world; had amused ourselves with its consequence, its taste, and its ton, till they ceased to be amusing…we left nought to regret at Cincinnati. The only regret was, that we had ever entered it; for we had wasted health, time, and money there.”

Although she was here a relatively short time, it cannot be disputed that Frances Trollope deserves a special spot in our local pantheon of female icons.

I just can’t believe nobody has reopened a Trollope’s Bazaar.