Single mothers and children hit hardest by poverty in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ranks second in the US for childhood poverty. Groups like The Women's Fund of The Greater Cincinnati Foundation are working to break down the barriers that keep single mothers from rising above the poverty line.

The U.S. Census Bureau reports that one in every three Cincinnatians lives below the federal poverty line. The city is ranked second in the nation for child poverty, according to the Children’s Defense Fund. Of those households, most are headed by single mothers.

So what can be done to break the cycle of poverty?

The Women’s Fund of The Greater Cincinnati Foundation believes the solution lies in ensuring the economic self-sufficiency of women in our region and igniting a shared desire to improve it. The organization focuses its efforts on raising women and girls out of poverty and strives to scratch beneath the surface of stereotypes surrounding the issue of poverty.

For instance, women living below the poverty line often qualify for vouchers to offset the cost of childcare. But once a woman’s income rises above the poverty line—even by a few dollars—she loses those vouchers, leaving her worse off financially than she was with a lower income. These types of catch-22s are what The Women’s Fund is working to combat.

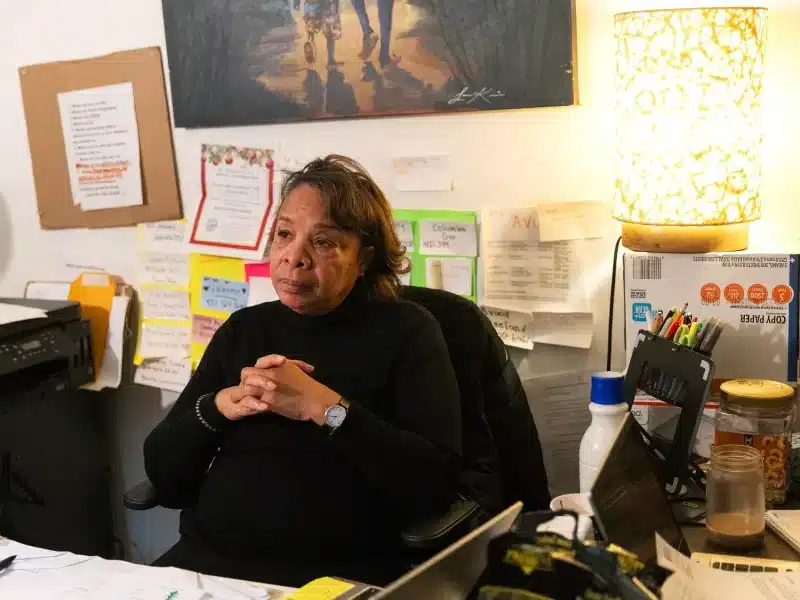

“In order to be self-sufficient, a woman with a child in preschool needs to make $17 to $18 per hour,” says Vanessa Freytag, executive director of The Women’s Fund.

But good-paying jobs and childcare are only part of the equation. Other concerns include affordable housing that’s not concentrated or located near public transportation, and access to job training and higher education.

For example, in 2009, the Board of Regents eliminated state-based financial aid from the Ohio College Opportunity Grant for students who attend public two-year institutions (students do qualify for federal aid such as Pell Grants). A more affordable first step toward a four-year degree, these institutions also provide job training for trades experiencing rapid growth, such as healthcare administration or manufacturing. But these changes have made access to that training less viable for those struggling with poverty.

“The community needs to understand why a family remains in poverty, particularly in female-headed households,” Freytag says.

Numbers talk

Most jobs being created today are in unskilled labor markets such as retail, fast food and other service-related industries. Low-wage work in Cincinnati accounts for nearly 60 percent of job growth, according to a report published by the National Employment Law Project. Minimum wage in the state of Ohio is $7.95 per hour.

Given these low wages, those experiencing poverty have limited housing options. In order to be considered affordable, housing costs cannot exceed more than 30 percent of household income, according to AHA, the Affordable Housing Advocates of Cincinnati.

A single mother who wanted to rent a two-bedroom apartment in Cincinnati without assistance would have to pay about $700 per month, the fair market rental cost, according to a report by the AHA. In order to afford that housing, she would have to earn about $28,000 annually. This would require an hourly rate of $13.46, given she works a 40-hour workweek.

A person making minimum wage would have to work about 68 hours a week to afford that same two-bedroom apartment. So it’s no surprise that an individual being paid minimum wage struggles with poverty and that a lack of affordable housing or a loss of income are the top two reasons for homelessness, says the Greater Cincinnati Homeless Coalition (GCHC). According to the Coalition, approximately 25,000 people in Cincinnati experience homelessness each year, and one quarter of the homeless population in Cincinnati is children.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hear the stories of two homeless Cincinnati residents and their paths to self-sufficiency.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Centralized poverty an issue

So affordable housing is a necessity, especially for those trying to climb out of poverty. Neighborhoods with a high poverty rate are typically sites of low-income or affordable housing development. Cincinnati recently approved plans for a 90-unit development project in Avondale that will provide high-quality permanent housing with supportive services targeted to serve formerly homeless and disabled individuals. Construction on the Commons at Alaska is set to begin by fall 2014.

Avondale 29, a coalition of homeowners located near the planned development site, is rallying against the plans. Members are concerned that the development will increase crime rates, will reduce property values and could lead to a concentration of poverty in a neighborhood that already experiences high crime and poverty rates.

“Five of the first 11 homicides of the year occurred in Avondale,” says Linda Thomas, president of the group. “Why would you continue to concentrate poverty in a neighborhood desperately trying to revitalize?”

Thomas says she believes that if the project continues, it will tilt the balance to a more transient rental environment, which is a concern of long-time homeowners.

“The negative impacts are real,” she says. “Not only does it impact children and families, it is well documented that high concentrated poverty has higher crime rates.”

The group plans to petition the Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority to not grant vouchers that would aid the developer with construction costs.

GCHC’s Anna Worpenberg, a proponent of the project, says the public must be educated on the subject to combat negative stereotypes of the homeless and poverty stricken.

“Many studies have been done on affordable housing. … Crime and neighborhood deterioration are not strictly due to affordable housing,” Worpenberg says.

GCHC provides many educational programs, including “Shantytown” during which participants experience what it is like to be homeless and the Streetvibes Selling Tour, which allows resident to shadow a distributor who sells the Coalition’s newspaper publication as a source of income.

Childcare costs create obstacles

The housing affordability equation does not take into account the amount of income spent on other expenses or household size. For example, access to public transportation or cost of fuel varies greatly along with other necessities, such as food. And working single parents have childcare expenses that retired or childless adults do not.

“The cost of childcare, in most cases, exceeds the cost of housing,” Freytag says.

The average annual cost of full-time childcare in Ohio ranges from $8,482 for an infant to $4,664 for school-age children, according to a report by Child Care Aware of America.

The Women’s Fund is attempting to address the high cost by providing gap funding for single mothers living in poverty. Initiated by Gateway Community Technical College, the Raise the Floor program seeks to help women gain manufacturing skills in that fast-growing job market in Northern Kentucky. The program began last summer with funding finalized in March.

“Individuals making over $10 per hour in the State of Kentucky do not qualify for childcare assistance,” Freytag says.

“Companies are beginning to recognize the challenges when trying to find qualified candidates that need childcare. As companies have juggled the challenge of health care, childcare assistance has taken a back seat.”

Participating companies or individual donors must match initial seed funding for the program. The goal is to provide up to $120,000 in funding per year for the next three years to help women afford the costs of childcare.

“It’s a challenge navigating the complex day for a single mother, or anyone in poverty,” Freytag says. “We must focus on where the jobs exist today … and what we can do to support the climb to becoming self-sufficient.”

The Women’s Fund sponsors exchanges and other programs to educate and create dialogue about poverty with the community. Each month, a panel of caseworkers and social workers attempt to navigate the challenges single parents in poverty face on a daily basis.

And they’re not alone in their efforts. Organizations such as 4c for Children, which operates in southwest Ohio and Northern Kentucky, provides resources for high-quality early childhood education and care. They also provide support for local families and service providers. Education, especially in certain trades, provides a stepping-stone for progress. It’s a start, and comes at a lower cost than most four-year universities.

In a time of rising costs, stagnant pay and a fight to increase minimum wage on Capitol Hill, The Women’s Fun and 4c for Children believe that strategic, community-centered initiatives are the key to winning the fight against poverty.

Matthew Woolley is a freelance writer and recent graduate of the University of Cincinnati. He served as Soapbox’s winter/spring intern. Follow him at @Cincy_Matthew.

Photography by Katie Dreyer.