Quality preschool key to lifelong success

Studies show that two years in a quality preschool can have an enormous impact on a child’s life trajectory — more than interventions at any other stage — but few families can afford it. Preschool Promise is a program aimed at closing that gap, and a new pilot program shows how universal access to quality preschool can work.

Steven’s* mother used to drive him four hours every day to stay with his grandmother in Indiana while she went to work. She had recently put herself through school and landed a good job in a dental clinic, but that meant she no longer qualified for childcare assistance from Jobs and Family Services. As a single mother of two, staying home wasn’t an option. But neither was paying for childcare out of pocket. The long commutes were making her late to work, and causing her son in elementary school to spend many hours alone at home each day as she ferried 4-year-old Steven between states.

Unfortunately, this isn’t such an unusual problem. The state of Ohio offers childcare assistance to parents in school, and those working but earning below 125 percent of the poverty rate. This sort of assistance was designed as a workforce support, providing a safe place for children to be during the day, but wasn’t established to fund enrollment in places of quality education.

Preschool and Poverty

An increasing body of research now shows that two years in a high-quality preschool program has a greater positive impact on a child’s development than interventions at any other stage, especially for those growing up at or near the poverty line. Evidence shows that many children in our city aren’t getting that head start.

In 2012, only 55 percent of students entering Cincinnati Public Schools kindergartens were assessed as ready to read. Fewer than half could recognize 18 or more lowercase letters of the alphabet. These figures are significant for the region, as students unprepared for kindergarten are 42 percent less likely to read at grade level by 3rd grade. At that point, students below grade reading levels are four times more likely to drop out of school, and 13 times more likely if they are also from low-income families. In this sense, low-income families beget low-income families, a trend that hits particularly close to home.

Cincinnati has the third highest poverty rate in the United States—34.1 percent of people here live below the poverty line. Further, we rank No. 2 in the country for child poverty, with more than half of the city’s children living in poverty in 2012.

In the face of such grim U.S. Census Bureau figures, the Cincinnati Preschool Promise initiative began studying economic, neuroscience and education research in order to find ways to change the trend.

“One of the most reliable strategies in terms of ending generation-based poverty is early learning, development and access to support during the first 1,000 days of child’s life,” says Greg Landsman, executive director of Strive Partnership, a parent organization of the Preschool Promise initiative.

Raising the Bar

Preschool Promise is an independent, cross-sector effort to provide universal access to high-quality preschool for all 3- and 4-year-olds in Cincinnati. Through work with United Way of Greater Cincinnati’s Success By Six and 4C for Children, they’ve identified some encouraging opportunities for positive change.

The Preschool Promise strategy is modeled on a program in Denver, which has increased its preschool enrollment tenfold in the four years since its inception. Today, the Denver Preschool Program enrolls 70 percent of area 3- and 4-year-olds in high-quality programs, and of those, 90 percent leave preschool ready for kindergarten.

But what differentiates “high-quality” preschool from ordinary childcare? Ohio’s Step Up to Quality and Kentucky’s STARS for KIDS NOW offer quality-rating systems for preschools and childcare centers. These ratings are designed to help parents understand the factors of quality in childcare and choose one that best matches their needs.

To earn a high-star rating in these systems, facilities must deliver everything from safe environmental conditions to suitable safety procedures, proper implementation of a curricula, good nutrition, individualized learning plans, staff training and low teacher-to-child rations. For instance, Ohio requires a staff to child ratio of 1:12 for 3-year-olds and 1:14 for 4-year-olds, but getting closer to a 1:6 ratio can help a provider earn more stars.

“Many childcare providers start off minimally with a license, but that’s a very nominal standard. The star system raises providers way above that,” says Karen Hurley, vice president for development and communication at 4C for Children.

4C is contracted by the state of Ohio to provide training and coaching to childcare programs so that they can become eligible for star ratings. 4C works with unrated childcare providers to help them meet criteria to earn a star, as well as providers already in the system that are working to earn more stars. The state then sends an inspector and awards a star rating based on the program’s performance.

“It takes a lot of work to move up that scale. You can’t just change a few things and get a star tomorrow; it may take a year to get to that rating,” Hurley says.

While universal access to high-quality preschool is the ultimate goal of 4C and Preschool Promise, the first step is making sure there are enough preschools in Greater Cincinnati that can provide the appropriate level of care. At the moment, there simply aren’t enough to accommodate all the region’s preschoolers. And for those that are meeting high-quality standards already, the costs of the time, money and staff investments required to reach those standards make enrollment difficult for parents to afford.

“Those that are achieving quality are sometimes begging for students,” Hurley says. “The dilemma is that the quality spaces we do have just aren’t being filled.”

Pitching the Investment

Overcoming this dilemma will mean persuading parents, childcare providers and the community that quality preschool is a good investment. Without the prospect of a broad tuition base to cover costs, preschools have little incentive to earn higher star ratings. But unless more preschools reach those ratings, tuition credits through Preschool Promise will have little more impact than the current system of basic state childcare assistance. For Preschool Promise to succeed, what’s needed is an investment to get the process started—and as far as investments go, the research coming out of Preschool Promise shows that early childhood education is one of the smartest bets we can make.

“This is a huge opportunity to change outcomes for thousands of children,” Landsman says. “And to improve schools throughout the city, as will happen when more and more children show up prepared: schools get better, and when schools get better they retain and attract families, which then helps neighborhoods grow. All of this combines to build a more competitive workforce.”

In fact, a little number crunching shows that if 70 percent of Cincinnati 3-year-olds attend two years of high-quality preschool, the aggregate economic benefits per enrolling class would be $48.4 million over each student’s working lifetime. This projection is based on the waterfall savings in school and remediation costs, increased parent productivity, reduced crime, criminal justice and social services costs, and higher tax revenue yielded by a stronger workforce. That’s an annual savings per enrollee of $12,942. Compare this with the $10,000 per year tuition that 4C for Children estimates for high-quality preschool enrollment, and it doesn’t take an accountant to see the long-term payoff.

So the figures show that early childhood education is a good community investment. But where does the money come from? The Denver Preschool Program pays for tuition credits with a voter-approved 12 cent sales tax on $100 purchases. Since 2006, the program has raised $40 million in tuition support and benefited more than 25,000 4-year-olds. This is just one measure that Preschool Promise is exploring for the funding of its program in Cincinnati.

“How we get there is debatable,” Landsman says, “but when you have something that has a very high success rate and a very strong return on investment—which is the case for quality preschool—people will rise to the occasion. Cincinnati is transitioning away from wondering if we can do big things to believing that we can do big things.”

Piloting the Strategy

And indeed, there is growing support for this mission. Last year Crossroads Church raised $150,000 for Preschool Promise. 4C administered the money, dividing it among four quality-rated preschools for tuition credits to families with income at or below 200 percent of the poverty level. The program kicked off in August and provided financial support to 32 preschoolers who wouldn’t otherwise have been able to attend quality preschool. This is where our story returns to Steven and his mother, for whom finding even basic childcare meant long commutes and job absenteeism.

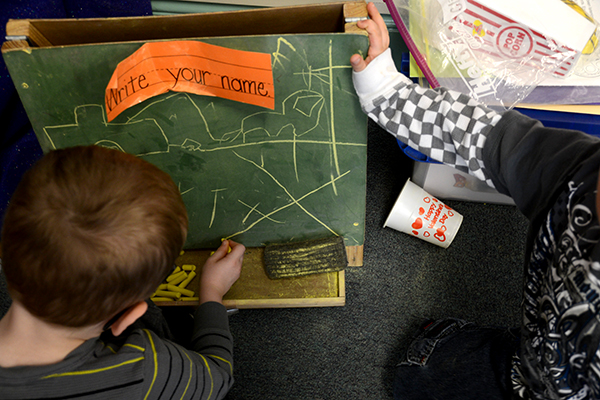

As Steven’s mother continued to miss more and more time at her newfound job, her boss inquired about enrolling Steven in the Preschool Promise pilot. Steven met the eligibility criteria and was accepted into the program. Now, thanks to the money raised through Crossroads Church, the strategic research done by Preschool Promise and 4C’s implementation, Steven is in an environment where he’s learning to read, socialize and develop habits that will help him to be successful in kindergarten. Moreover, his mother regularly arrives to work on time and is able to pick up her older son every day after school rather than leaving him to get home on his own.

“We know for a fact that this mom really worked hard to ensure the wellbeing of her family by advancing her own career, and as a result she found it difficult to maintain her childcare,” says Carolyn Brinkmann, director of parent services at 4C for Children. “We’re trying to get our dollars to stretch as far as possible for these most vulnerable families and children.”

Steven’s story is a realization of Preschool Promise’s vision on a miniature scale. As children are put on a better course for their own lives, and parents can spend more quality time at work and with their children, families in Cincinnati have an opportunity to rise out of the cycle of poverty.

Landsman expects Preschool Promise to find its financial footing within a year or so. The pilot has shown that the program can work, and that there is both need and desire in the community for high-quality preschool programs. The next stage for Preschool Promise is to use this evidence to establish broad-based community support and parent input on what they want to see, how they want it to work and how the program should be financed.

“Now is the time to make the case for additional and significant public support for this,” Landsman says. “Ultimately we want to put forward something that has been developed and is owned by this community. Every year we wait, we lose an entire cohort of children who will struggle to make it through no fault of their own.”

*”Steven’s” name has been changed to protect the family’s privacy.