Innocence Project Brings World to Cincinnati to Highlight Global Human Rights

The Ohio Innocence Project has attracted national attention to UC’s College of Law for it’s long list of successful exonerations of wrongfully convicted individuals. This week OIP and it’s director, Professor Mark Godsey, will once again be in the limelight as host of the first globally focused Innocence Network Conference that also includes a moving display of artwork created behind bars by exonerees.

Mark Godsey’s office in the UC College of Law looks like a cross between a paper company explosion and a moving company warehouse.

Part of that is because he is storing newspaper-covered artwork created by former prison inmates until they are installed at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center for an exhibit that opens April 7. Another part is because he has more than 200 boxes of Girl Scout cookies stacked around him, ready to distribute for his 11-year-old daughter. But mostly, it’s because Godsey sits in the eye of a hurricane of important civil and human rights’ work.

The law professor and director of the Lois and Richard Rosenthal Institute for Justice/Ohio Innocence Project lives his days in clearly defined increments- typically 15 minutes – that allow few spare moments for filing and straightening. “The typical day can only be described in the abstract,” says the 42-year-old father of two. When he’s working, it’s like a full-on faucet pouring confetti in front of a fan.

For more than two years, one steady stream of the faucet has been aimed at organizing the first-ever internationally focused Innocence Network Conference: An International Exploration of Wrongful Conviction, at Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, April 7-10.

Since the late 1980s, the innocence movement has inspired the creation of dozens of Innocence Projects around the country. Those projects have helped exonerate more than 200 men and women who were wrongfully convicted, many times by using DNA evidence to reopen and retry closed cases.

The Ohio Innocence Project, founded at the University of Cincinnati Law School in 2003, has a staff of three attorneys and 20 law students who investigate DNA and non-DNA cases after careful consideration. Work by the Ohio Innocence Project has led to more than 10 exonerations, including the release of Raymond Towler, who had been unjustly imprisoned for 29 years for rape and assault.

Just as importantly, the project has spearheaded significant legislative reform. Ohio’s Senate Bill 77, signed in April 2010, made national headlines because of its comprehensive approach to innocence protection, including requiring police to hold on to DNA evidence for up to 30 years in murder and sexual assault cases.

“Our clients have not had the benefit of the way our system is supposed to work,” says OIP attorney Karla Hall. “By the time they get to us, they have already exhausted all the options they have.” She estimates that while the project receives hundreds of requests for help, staff members choose to take on about only about 3 percent of them. Only about 1 percent of the cases they investigate wind up at trial.

On Hall’s first day on the job three years ago, she received three cases – one that involved DNA and two that did not. Inmates in both of the non-DNA cases have been exonerated this year. She won the fight to have the DNA case investigation reopened, but missing evidence indefinitely stalled any chance of reconsideration. “Whether we win or not,” Hall says, “we know we have done everything that we can.”

At annual innocence network conferences, Hall enjoys celebrating the hard-won victories of her peers, lawyers who work long hours for low pay, serving clients who pay no fees. “We inspire one another,” she says. This year, she looks forward to meeting with attendees from countries where the very concept of an innocence project remains a distant dream. Representatives from China, Nigeria and Pakistan, as well as from nations throughout the European Union, will gather to hear from human rights scholars, innocence project experts and the largest gathering of exonerees in history.

“The impact is going to be more far-reaching than our city,” Hall says. “It’s going to be an amazing opportunity to learn from each other.”

Godsey has learned a lot about the grueling and politically challenging work of overturning convictions since he took the OIP job in 2003. He came to Cincinnati with experience on both sides of criminal cases, having served as an assistant US attorney in New York, where he worked with the FBI to investigate the Gambino crime family, and as a defense attorney who donated significant hours as a public defender in Chicago and New York.

He expects 500 attendees at this month’s conference, which he calls his “baby.” One hundred of those attendees will be exonerees, making it the largest gathering of exonerees in history. While yearly sessions give former inmates chances to connect and share stories, this year the conference also provides a unique feature: a public space to display artwork they created while still behind bars.

“Illustrated Truth: Expressions of Wrongful Conviction” opens the same day as the conference, and includes “Expressions of the Wrongly Convicted,” a gallery of visual art and writing by exonerees. Some pieces are understandably political. For example, “Flood of Lies” by Al Cleveland, currently serving 14 years of a life sentence for murder, features a single hand reaching out of an ocean as if in a last gasp before drowning.

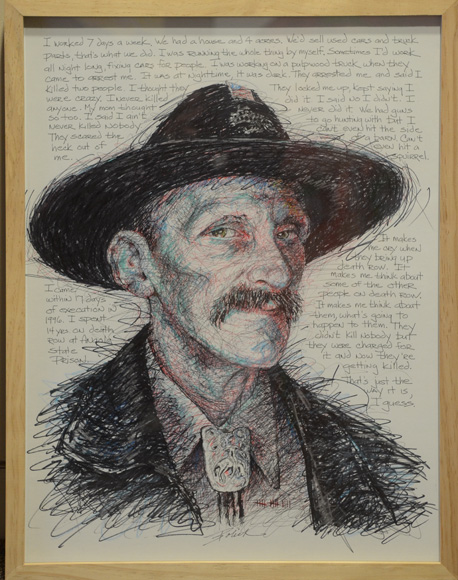

Another element of the Freedom Center exhibit is a collection of 13 larger-than-life portraits of exonerees by Daniel Bolick. Bolick, who spent 34 years as an art teacher in Pittsburgh’s public school system, hopes people who see the portraits never forget the anger, bitterness, hope, acceptance and salvation captured in the expressions of his subjects, who together spent more than 200 years in prison.

The final piece of the “Illustrated Truth” exhibit is dedicated to “The Innocents,” which features artist Taryn Simon’s photographs of men and women who spent time in prison for violent crimes they did not commit. Simon photographed “The Innocents” at sites significant to their cases. Some were photographed at the scenes of the crimes they did not commit, others at the sites of their arrests or alibis.

Godsey sees a natural connection between art and the experiences of those who have been wrongly convicted. He was inspired by the gift of a painting of a warrior by a current client, Roger “Dean” Gillispie, who has been imprisoned for nearly 20 years for kidnapping and raping three women, crimes Godsey strongly believes he did not commit. Godsey began to have conversations with others involved with the innocence movement about the artwork that their clients produce as they struggle to find constructive ways to express their thoughts and feelings. “The wrongfully convicted have important things to say, and it is clear that art is a particularly powerful and effective way for them to say it,” Godsey notes in the newest issue of The Freedom Center Journal, a bi-annual publication of the UC College of Law.

The Freedom Center Journal published to coincide with the conference includes an extensive collection of exoneree stories and artwork that range from wistful to frustrated to hopeful. Steven Barnes, who served 19.5 years in prison for a rape and murder that he did not commit, painted “Covered Bridge” as an expression of a beautiful world he hoped to rejoin. Julie Rea, who served two years of a 65-year sentence for the murder of her only child before being exonerated, crafted a collage rich with reminders of her former life while she wrote about finding refuge through tea time with other inmates. “Hands,” a black-and-white drawing of three hands drooping out from behind prison bars, represents some of the half-of-a-lifetime, or 26.5 years, that the late Timothy Howard spent in prison for an aggravated murder and robbery he did not commit.

Powerful and at times confrontational, inmate artwork does more than help the prisoners express themselves. Godsey has a special spot for the painting Roger “Dean” Gillispie gave him. “As Long as there is One,” which is featured in the latest Freedom Center Journal, does not hang in Godsey’s crowded office. It hangs in a special spot just outside his bedroom door where he can see it first thing every morning. It serves as a constant inspiration, and a reminder of the necessity of the work he, his staff and his students do every day.

The artist wrote a message to Godsey on the back of the artwork: “This painting of a warrior was painted by a warrior, “Dean ‘Spiz’ Gillispie” for a warrior, “Mark Godsey,” who has fought, is fighting and will continue to fight for the innocent, as long as there is one.”

Gillispie’s next step toward potential exoneration, a federal hearing at which Godsey and former Ohio Attorney General Jim Petro will represent him, is slated for later this month. If Godsey has his way, the Ohio Innocence Project will be able to claim one more exoneree before “Illustrated Truth” ends its run at the Freedom Center in July.

Photographs by Scott Beseler.